In most countries around the world, 2011 saw the writings of F. Scott Fitzgerald enter the public domain. Scott Donaldson, author of the biography Fool For Love: F. Scott Fitzgerald, explores the obscuring nature of his legend and the role that women played in his life and work.

With Fitzgerald as with no one else in American literature save Poe, the biography gets in the way. Never mind that F. Scott Fitzgerald is the author of one exquisite short novel as perfect as anything in our literature and of another longer, more chaotic novel of tremendous emotional power. Never mind that he has written a couple of dozen stories that by any standard deserve the designation of “masterful.” Ignoring those legacies, much of the general public still tends to think of him in connection with the legends of his disordered and difficult life, and to classify him under one convenient stereotype or another. So diminished in stature, Fitzgerald becomes the Chronicler of the Jazz Age, or the Artist in Spite of Himself, or – most prevalent stereotype of all – the Writer as Burnt-Out Case: a man whose tragic course functions as a cautionary tale for more commonsensical aftercomers. His saga offers an almost irresistible temptation to sermonizers, overt or concealed. It is not right to ride on top of taxicabs or disport oneself in the Plaza hotel’s fountain, not right to drink to excess or abuse a “lovely golden wasted talent.” Go thou and do otherwise.

This warning usually remains implicit, of course. It is not the homily but the tale of star-crossed lovers that commands attention – handsome brilliant erratic Scott married for good or ill to beautiful willful unstable Zelda. There is an arresting poignancy in the way the two of them – Scott more than Zelda, perhaps – considered the alternatives and chose the sweet poison. Somehow, in the repeated retellings of this tale, the Fitzgeralds have come to stand for a kind of generic nonspecific glamour, now sadly departed. In 1980 the opening party for an exhibit of Fitzgeraldiana at the National Portrait Gallery drew an enormous crowd determined to celebrate a vanished past. The band played Glenn Miller and Benny Goodman numbers from the 1940s, the decade following Fitzgerald’s death. A few women attempted flapper costumes, but for the most part the clothes were as anachronistic as the music. One chap, aiming for colonial elegance, danced in a pith helmet. The details that mattered so much to Fitzgerald, a man precisely in tune with his times, mattered very little to those come to the party to memorialize his legend. Zelda and Scott, Scott and Zelda – they are fixed so securely in the collective mind as lovable reckless youths for whom it all went disastrously wrong that it has been difficult to set that image aside and concentrate on the work that established him as one of the major literary artists of the twentieth century.

Henry James, himself a biographer as well as a novelist, understood that the entire truth about anyone could never be told. “We can only take what groups together,” he said. What most grouped together in Fitzgerald’s work and life, I came to realize over several decades in the classroom and five years of intensive research, was an overweening compulsion to please. He wanted to please other men, but did a poor job of it. His Princeton classmates considered him over-inquisitive and frivolous. Zelda’s father thought him unreliable. Ernest Hemingway, the closest of friends in the mid-1920s, eventually came to regard him with something like scorn. Fitzgerald was far more successful in pleasing women. Readers of his fiction might expect as much, for he is one of our more androgynous writers, with a rare capacity to put himself in the place of characters of either sex. “All my characters are Scott Fitzgeralds,” he acknowledged. “Even my female characters are feminine Scott Fitzgeralds.” The set of instructions Fitzgerald drew up, at 18, for his younger sister Annabel provides convincing evidence along these lines. In this remarkable document he coached his sister in the finer points of attracting boys: how to groom herself, how to dance, what to talk about, how to flatter. And the androgyny is everywhere evident in the stories and novels, too, which is probably why most female college students are attracted to his fiction.

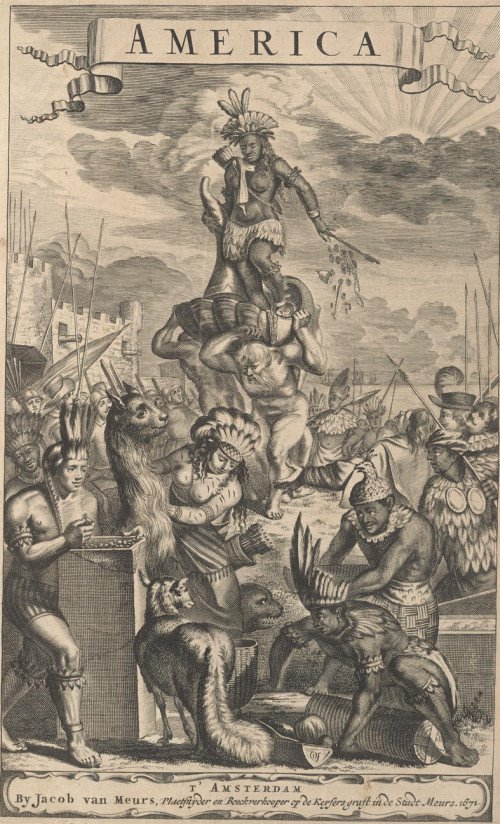

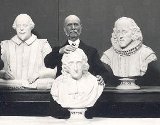

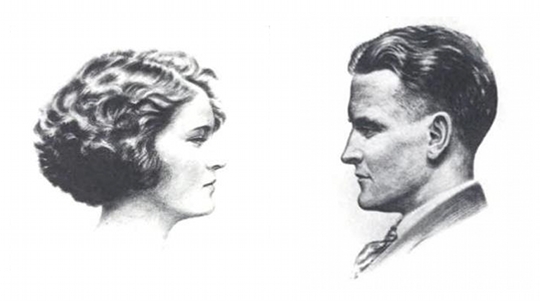

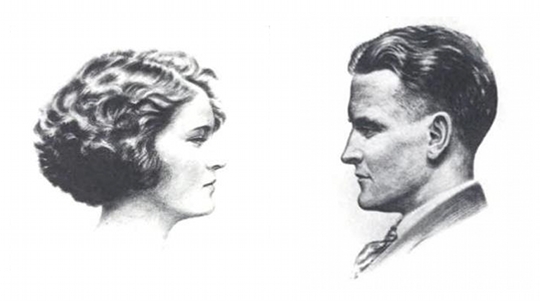

Left: Image of Zelda published in Metropolitan Magazine in June 1922, accompanying her piece "Eulogy of a Flapper". Right: A study of F. Scott Fitzgerald by Gordon Bryant, published in Shadowland magazine in 1921.

Equipped with this sensitivity, Fitzgerald played the game of courtship well. As a youth he was a notoriously successful flirt. “I’ve got an adjective that just fits you,” he would tell a dancing partner early in the evening, and then withhold the laudatory word to build up her expectations. He was good-looking, and at ease in the company of girls. He listened to them as few other boys did, and made it clear that he cared tremendously what they thought of him. Later, as a married man, he continued to woo women. He couldn’t help it. He needed their approval, which is to say their love and adoration. Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald may have been the most important woman in his life, but she was not and could not be the only one.

Fitzgerald suffered a tremendous setback when Ginevra King of Lake Forest, north of Chicago – one of the wealthiest and most beautiful debutantes of her day – spurned him in order to marry a young man of her own class. The rejection devastated Fitzgerald, even as it supplied him with the basic subject matter of much of his fiction. There are probably more characters in his stories and novels modeled on Ginevra than on Zelda Sayre, who caught him on the rebound. By altering the circumstances of the plot, Fitzgerald played variations on the age-old theme of the battle of the sexes.

Left: Fitzgerald reading alone in 1920. Right: Fitzgerald reading aloud to his friends in 1917, left to right, Helen Floan, Sidney Strong, Grace Warner, and Lucius P. Ordway, Jr. (Source: Minnesota Historical Society)

What is unusual about Fitzgerald’s treatment of this theme is its escalation – in the work as in the life — from the courting game of his adolescence to the fierce battle of his young manhood to the outright war of his maturity. Perhaps, we are inclined to think, Amory Blaine will not suffer unduly from his jilting by Rosalind Connage in This Side of Paradise (1920), Fitzgerald’s first novel. But Gatsby dies for Daisy in his 1925 masterpiece, and Dick Diver is stripped of his vitality and tossed aside by Nicole and her family in 1934’s Tender is the Night. In Fitzgerald’s fictional treatment of the war between the sexes, it is almost always the man who ends up defeated. By repeatedly depicting the downfall of his male figures, Fitzgerald was imagining what might well have happened (had not Zelda been afflicted with schizophrenia) and also – it seems to me – excoriating himself for his weaknesses. Tender, in particular, is a novel about the enervating effects of charm. Compelled to please everyone around him (and particularly women), Diver dissipates away his life’s work and his usefulness as a human being. The real Fitzgerald, like his invented protagonist, came to despise himself for this “fatal pleasingness,” a self-disgust that characteristically emerged under the influence of alcohol. Drinking runs like an inner malaise through Fitzgerald’s life and that of many of his male characters. His triumph came in the last years of his life, when – supposedly down and out in Hollywood – he cast aside this obsession, quit drinking, and went back to being what he called “a writer only.”

One of America’s leading literary biographers, Scott Donaldson has written eight books about 20th century American authors. These include Poet in America: Winfield Townley Scott (1972), By Force of Will: The Life and Art of Ernest Hemingway (1977), Fool for Love, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1983), John Cheever: A Biography (1988), Archibald MacLeish: An American Life (1992), winner of the 1993 Ambassador Book Award for biography, Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship (1999), Edwin Arlington Robinson: A Poet’s Life (2007), named the best biography of the year by Contemporary Poetry Forum, and Fitzgerald and Hemingway: Works and Days (2009). This present article is excerpted from the preface to a new paperback edition of his Fool for Love: F. Scott Fitzgerald from the University of Minnesota Press.

Links to Works

- This Side of Paradise (1920)

- Flappers and Philosophers (1921)

- The Beautiful and Damned (1922)

- Tales From the Jazz Age (1922)

- The Great Gatsby (1925)

- Tender Is the Night (1934)

- The Complete Pat Hobby Stories (1962)