Of all the attempts throughout history to geographically locate the Garden of Eden one of the most compelling was that set out by minister and president of Boston University, William F. Warren. Brook Wilensky-Lanford looks at the ideas of the man who, in his book Paradise Found, proposed the home of all humanity to be at the North Pole.

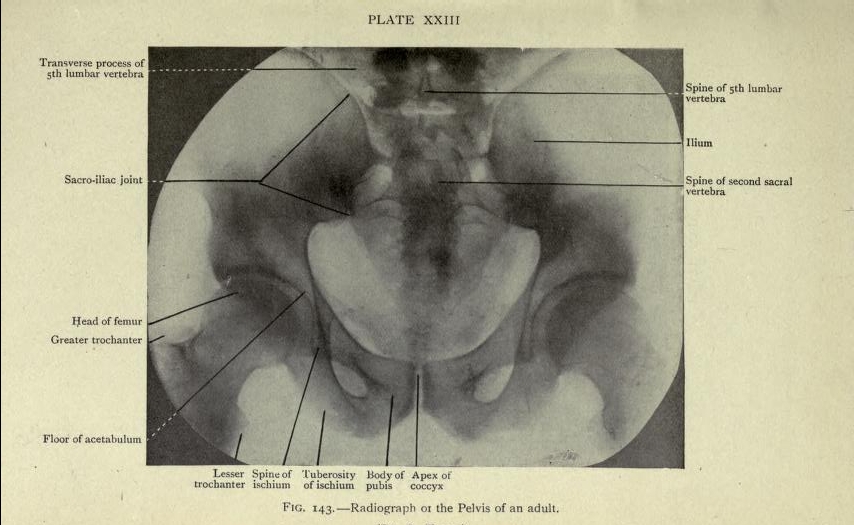

Map showing the geographical centrality of the North Pole, from Paradise Found (1885), by William F. Warren.

The quest to find the Garden of Eden sounds like an occupation that should have fallen by the wayside well before the nineteenth century. No longer did the fanciful medieval geographies of Prester John, or Columbus, allow for the existence of an exotic, unspoiled earthly paradise. This was a newer, wiser age. We had conquered the wild regions of the world. And Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in 1859, was slowly proving that man and, say, the birds of the air, were not created all at once in a single spot on the globe.

Darwin himself dismissed the search for a geographical point of origins in his 1871 Descent of Man. He allowed that: “It is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere.” But, he declared, there was also a large ape that roamed Europe not so long ago, and anyway the earth is old enough for primate species to have migrated all the way around it by now. So, “It is useless to speculate on this subject.”

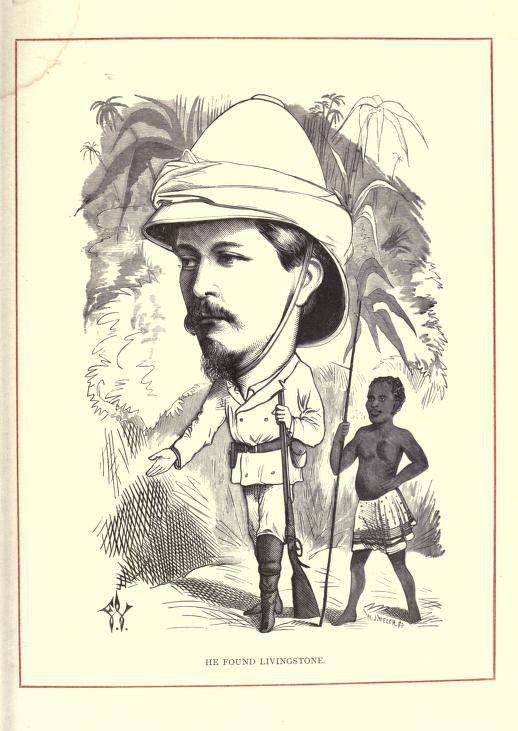

Victoria Woodhull, feminist radical and free-love advocate, was less diplomatic in her epic speech “The Garden of Eden,” which she delivered frequently in the 1870s. Eden on Earth was nonsense: “Any school boy of twelve years of age who should read the description of this garden and not discover that it has no geographical significance whatever, ought to be reprimanded for his stupidity.” (Perhaps she was referring to the missionary-explorer David Livingstone, who had declared, while mad with malaria in 1871, that paradise existed at the source of the Nile, which he judged to be in the Lake Bangweulu region of Zambia.)

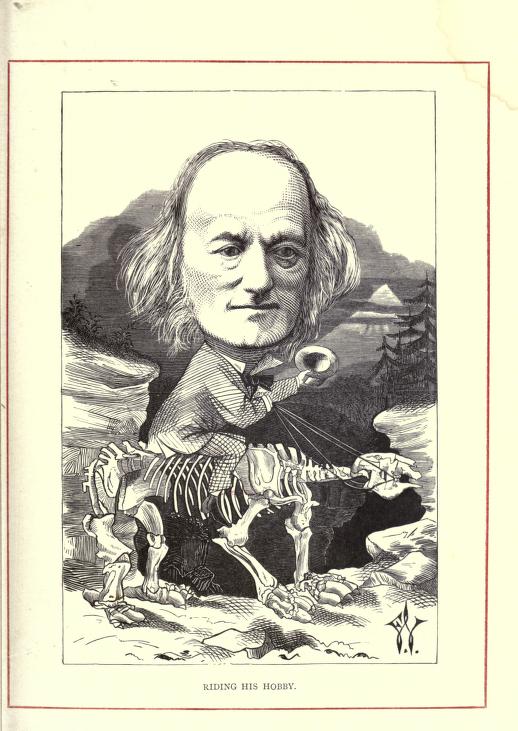

Livingstone was not the only one still looking for Eden. This brave new world was turning time-honored beliefs upside down. Evolution was suggesting that man had ascended over time from our less-intelligent, animalistic primate origins. But Christianity had been insisting for centuries that man had descended, through original sin, from near-divine heights in the Garden of Eden to the miserable, depraved society of the late nineteenth century. What was a modern, faithful person to believe? Enter William Fairfield Warren, distinguished Methodist minister and educator. As the president of Boston University, he knew science was going to define the future. But he was unwilling to give up his theology to the new discipline. How to knit the two perspectives together?

Counter-intuitively, Warren looked to Eden. He set about translating the Bible into science: Eden was “the one spot on earth where the biological conditions are the most favorable.” Genesis says Eden contains “every tree that is pleasant to the eye or good for food”; Warren posited “flora and fauna of almost unimagined vigor and luxuriousness.” He took note of a newly discovered fact: millions of years ago, the earth had been much warmer. He followed the uncovering of fantastic creatures at once familiar and mythical, like the woolly mammoth, the dinosaur, and the giant sequoia. He knew there was still one blank spot on the world map, a place where nobody had been. And he arrived at the inevitable conclusion: The Garden of Eden is at the North Pole. It made sense, in a way. Both Eden and the Pole had frustratingly resisted attempts to discover and claim them, despite centuries of dangerous, expensive expeditions.

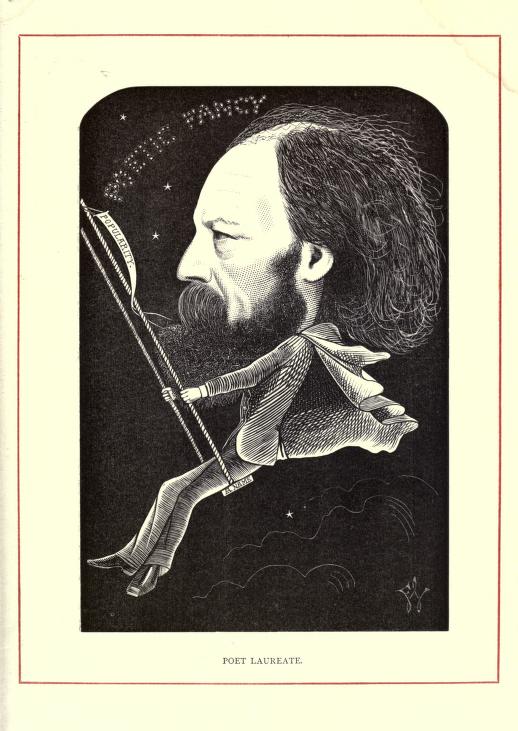

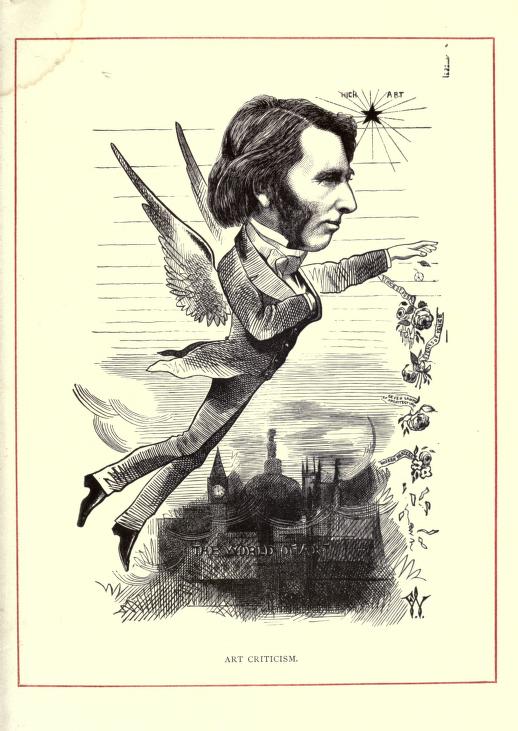

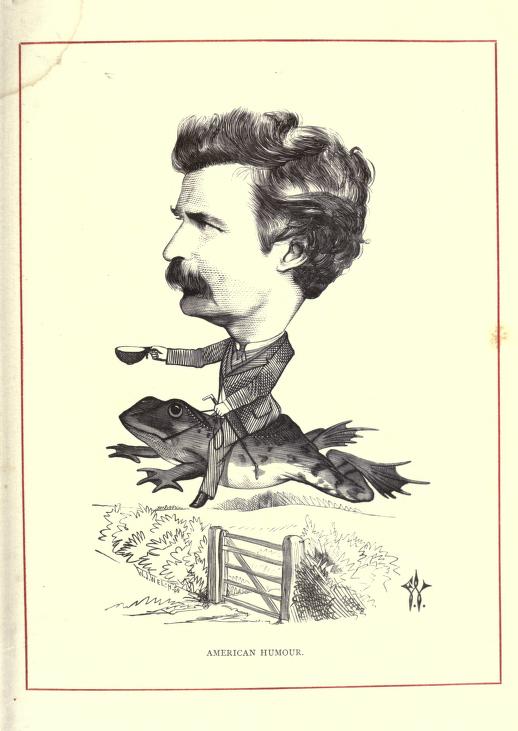

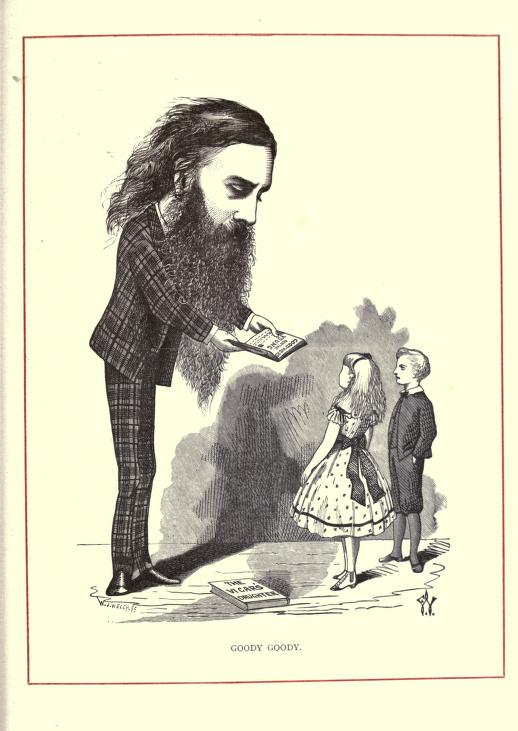

Illustration from Paradise Found (1885), by William F. Warren.

Warren published this theory in 1881 as Paradise Found, The Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole. The tome positively reeked with academic authority. There were long passages in French, German, and ancient Greek in the footnotes. He drew on his specialty, comparative mythology, which he described as “the science of the oldest traditional beliefs and memories of mankind.” He knew the great epic folklore of the Hindus, the Celts, the Chinese, the Persians. In the nineteenth century, this was a rare, esoteric body of knowledge, full of metaphorical echoes of Bible stories, objective “evidence” of Christian facts. The index of “authors referred to or quoted” in Paradise Found lists 580 sources — for 495 pages of text. Right next to Darwin there’s Ignatius Donnelly, who claimed that the lost continent of Atlantis was real; it was destroyed by the near-collision of the earth with a comet. His 1882 book Atlantis was wildly popular. (Donnelly had another theory — that Shakespeare’s plays might actually be written by Francis Bacon — but at the time that was considered too ridiculous to be taken seriously.) Some reviewers felt that Warren’s wanton citation did his argument no favors, but apparently many readers weren’t bothered.

The second printing of Paradise Found, released only months after the first, was peppered with testimonials. Warren wrote proudly of a “plain unschooled Bible student,” Mr. Alexander Skelton, a machinist and blacksmith of Paterson, New Jersey, who had independently arrived at his own “remarkably comprehensive and cogent” argument for a North Pole Eden. Warren bragged that one Professor Heer, a haughty Swiss paleontologist, claimed that Warren was plagiarizing him. He also published a testimonial from the British archaeologist, and faithful Anglican, Archibald Henry Sayce: “Provisionally, I may say that your view seems to me eminently reasonable…” (No matter that Sayce was actually referring to an earlier work of Warren’s, about the cosmology of Homer’s Iliad.) Warren’s theory was “rapidly superseding every earlier hypothesis” on both sides of the Atlantic— even if Warren did say so himself.

So it was a matter of confounding frustration for him that other Eden theories continued to appear. A German archaeologist, Moritz Engel of Leipzig, had the gall to publish The Solution To the Paradise Question simultaneously with Paradise Found. Engel’s Eden was an oasis in the desert outside of Damascus. His four rivers were flood torrents that disappear in the dry season, come May or June. Warren fought back: Engel’s Eden was ugly. It was as if Mr. Engel had never even read Genesis, with its picture of abundance and plenty! It was also narrow-minded, as if he never even noticed that there were “myths of the Happy Garden” found in dozens of other ancient traditions! Worst of all, Engel’s Eden was unscientific, making no effort to incorporate “the facts and theories of ethnologists and zoologists as to the beginnings of human life…. The time for studies of such narrowness as this is past.”

Warren’s insistence that the North Pole Eden was the overriding, authoritative account was sincere. But it may have been a little naïve, given the secret that Warren himself revealed on the very last page of his book: he didn’t actually think his paradise could be found. He writes, mournfully: “Long-lost Eden is found, but its gates are barred against us. Now, as at the beginning of our exile, a sword turns every way to keep the Way of the Tree of Life…” Arriving at Polar Eden, we could do nothing “but hurriedly kneel amid a frozen desolation and, dumb with a nameless awe, let fall a few hot tears above the buried and desolated hearthstone of Humanity’s earliest and loveliest home.” The only way to get back to Eden was in death, if we accept the sacrifice of Christ. Follow Jesus in life, and in death you can walk right past the cherubim with their flaming swords.

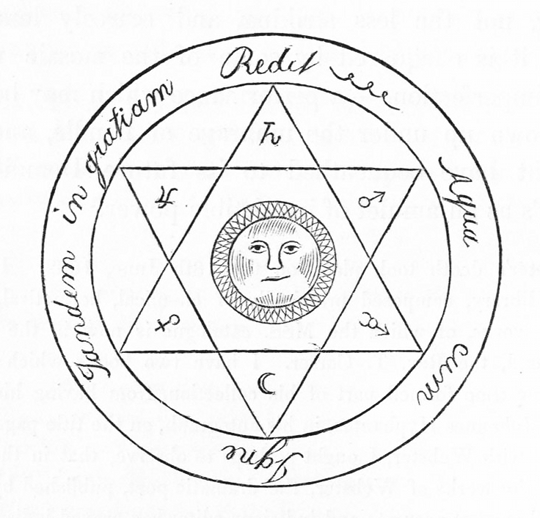

Frontispiece from Paradise Found (1885), by William F. Warren.

And just like that, despite his best efforts to be the last word on Eden, Warren had inadvertently opened the door for a whole new generation of Eden-seekers. They began to pop up almost immediately, and many even cited Warren as authoritative evidence for their own claims, just as Warren had done with his 580 sources.

It started with Warren’s own colleagues in the Methodist church. Reverend E. D. Ledyard announced to an audience of 5,000 at a retreat in upstate New York that Eden was rather closer to home. “In Chautauqua we see one place where Edenic privileges have been restored. Christ is the central figure here. Through the second Adam paradise is being regained.”

In 1890, a three-part editorial in the San Jose, California evening paper entitled “Garden of Eden: Its Position on the Globe Has Been Definitely Located” explained that California’s Santa Clara Valley had all the characteristics of an Eden—pristine state, perfect climate, and the giant sequoia. If Warren was so enthused about the sequoia, the writer notes, why didn’t he choose California? “In coming so near the truth it seems strange that the able scientific writer did not receive the true light as to the location of the original home of man.”

Warren can’t have been happy to find his work praised by Wyoming novelist Willis George Emerson, in the preface to his 1908 science fiction novel The Smoky God. The book claimed to be the true account of a Norwegian fisherman who in 1829 had fallen through a hole at the North Pole into the interior of the Hollow Earth — where the Garden of Eden is reachable by monorail. “In his carefully prepared volume, Mr. Warren almost stubbed his toe against the real truth, but missed it seemingly by only a hair’s breadth.”

Dr. George C. Allen, a Boston University philologist, took his colleague Warren’s word for it that Eden was at the North Pole. But he made one important modification. In 1921, he claimed that the North Pole moves entirely around the world every 25,000 years, so “careful mathematical computations bring the original paradise where Ohio now is.”

Warren himself, who died in 1929 at the age of 96, remained utterly, evangelically convinced of his original theory’s veracity. The North Pole Eden “has shown itself the supreme and inevitable generalization from all the facts of modern knowledge respecting man and the world. It has harmonized the oldest traditions of religion and the latest achievements of science…”

But a dead Eden and the promise of a more perfect afterlife did not satisfy the same kind of itch for a living paradise — an itch that had turned out to be peculiarly modern after all. Invisible paradise after death was too remote to be believed. And so a surprising number of twentieth-century thinkers continued to try to bring Eden down to earth. Reverend Landon West, an Anabaptist minister in Ohio, insisted in 1901 that the giant earthwork known as the Serpent Mound, outside Chillicothe, marked the site of man’s first transgression. Hong Kong Christian revolutionary Tse Tsan Tai believed that placing Eden in Outer Mongolia could help bring about an end to World War I. Libertarian lawyer Elvy Edison Callaway used numerology to prove that God had made man in the Florida Panhandle; in 1956 he opened a park for all to visit. And like William Warren, each of these seekers were working to synthesize their time-honored religious beliefs with the requirements of modern science. That’s a quest that continues to this day.

Brook Wilensky-Lanford is the author of Paradise Lust: Searching for the Garden of Eden (Grove Press), just out in paperback. She writes about religion and culture for the Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, Lapham’s Quarterly, and Killing the Buddha, where she is an editor.

(Grove Press), just out in paperback. She writes about religion and culture for the Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, Lapham’s Quarterly, and Killing the Buddha, where she is an editor.

Links to works

Paradise Found, the cradle of the human race at the North Pole: a study of the primitive world (1885), by William F. Warren.

The Smoky God or, A voyage to the inner world (1908) by Willis George Emerson; with illustrations by John A. Williams.

Sign up to get our free fortnightly newsletter which shall deliver

direct to your inbox the latest brand new article and a digest of the

most recent collection items. Simply add your details to the form

below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your

subscription!

Sign up to get our free fortnightly newsletter which shall deliver

direct to your inbox the latest brand new article and a digest of the

most recent collection items. Simply add your details to the form

below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your

subscription!