In 1884 Edwin Abbott Abbott published Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, the first ever book that could be described as ‘mathematical fiction’. Ian Stewart, author of Flatterland and The Annotated Flatland, introduces the strange tale of the geometric adventures of A. Square.

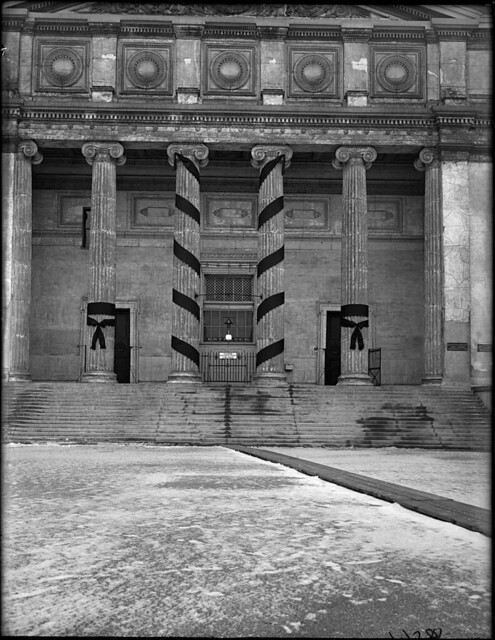

Edwin Abbott Abbott, who became Headmaster of the City of London School at the early age of 26, was renowned as a teacher, writer, theologian, Shakespearean scholar, and classicist. He was a religious reformer, a tireless educator, and an advocate of social democracy and improved education for women. Yet his main claim to fame today is none of these: a strange little book, the first and almost the only one of its genre: mathematical fantasy. Abbott called it Flatland, and published it in 1884 under the pseudonym A. Square.

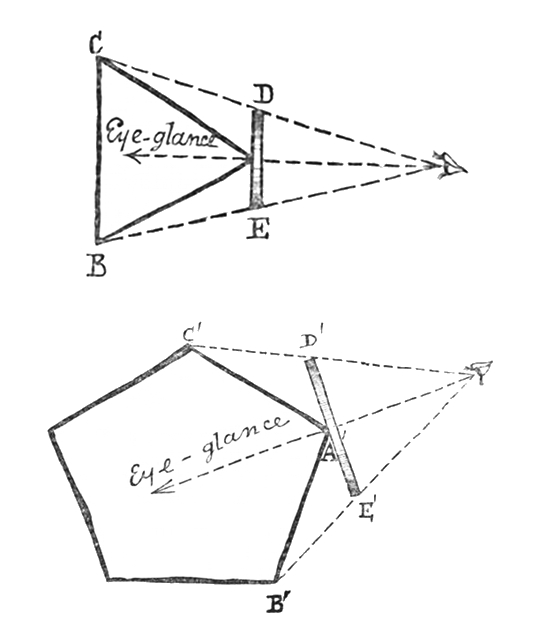

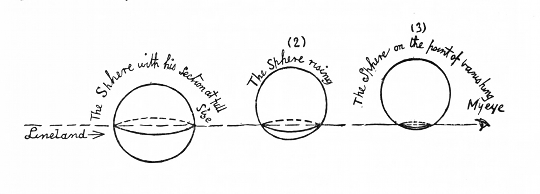

On the surface — and the setting, the imaginary world of Flatland, is a surface, an infinite Euclidean plane — the book is a straightforward narrative about geometrically shaped beings that live in a two-dimensional world. A. Square, an ordinary sort of chap, undergoes a mystical experience: a visitation by the mysterious Sphere from the Third Dimension, who carries him to new worlds and new geometries. Inspired by evangelical zeal, he strives to convince his fellow citizens that the world is not limited to the two dimensions accessible to their senses, falls foul of the religious authorities, and ends up in jail.

The story has a timeless appeal, and has never been out of print since its first publication. It has spawned several sequels and has been the subject of at least one radio programme and two animated films. Not only is the book about hidden dimensions: it has its own hidden dimensions. Its secret mathematical agenda is not the notion of two dimensions, but that of four. Its social agenda pokes fun at the rigid stratification of Victorian society, especially the low status of women, even the wives and daughters of the wealthy.

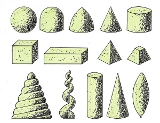

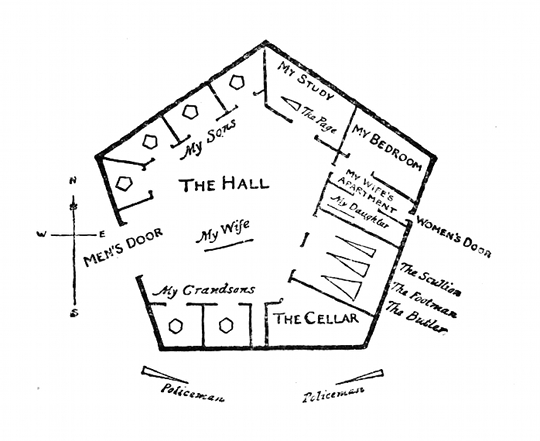

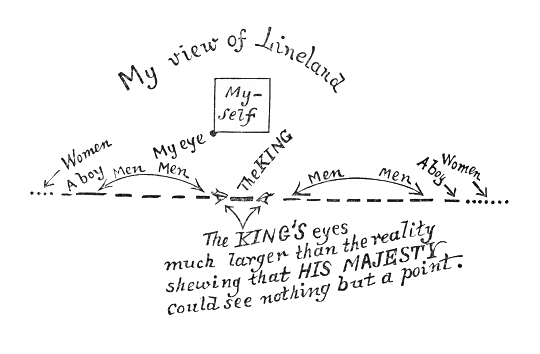

Flatland’s inhabitants are triangles, squares, and other geometric figures. In the planar world’s orderly hierarchy, one’s status depends on one’s degree of regularity and how many sides one has. An isosceles triangle is superior to a scalene triangle (all sides different) but inferior to an equilateral triangle. But all triangles must defer to squares, which in turn defer to pentagons, hexagons, right up to the pinnacle of Flatland society, the Priestshood. Referred to as ‘circles’, the priests are actually polygons with so many sides that no one can distinguish them. The sons of squares are usually pentagons, the grandsons hexagons, so there is a general progression along the greasy pole (there is no ‘up’ in Flatland).

But what of the wives and daughters? Flatland’s women are mere line segments, actually very thin triangles, whose social standing is zero. Their intelligence is little greater. They are required by law to wiggle from side to side so that they can be seen, and to emit loud cries so that they can be heard, because a collision with a woman is as fatal as one with a stiletto. Abbott took a bit of stick from some of his female contemporaries, who failed to appreciate his irony. But we know from his own life, including his daughter’s education, that he did a lot to improve the status of women and to ensure they received the same level of education as men.

Abbott wasn’t particularly good at, or keen on, mathematics, but his book tackled an issue of great interest in Victorian times, the notion of four (or more) dimensions. This idea was becoming fundamental in science and mathematics, and it was also being invoked in areas like theology and spiritualism, because an invisible extra dimension was just the place to locate God, the spirit world, or ghosts. Charlatans like the American medium Henry Slade were exploiting conjuring tricks to claim access to the Fourth Dimension. Legitimate hyperspace philosophers were speculating about the role that additional dimensions might play in illuminating the human condition.

Flatland approaches this topic by way of a dimensional analogy, widely used ever since, and not entirely Abbott’s own invention. The difficulties facing a three-dimensional Victorian attempting to grasp the geometry of four dimensions are similar to those facing A. Square attempting to grasp the geometry of three. Among Abbott’s sources for this analogy were frequent social encounters with eminent scientists such as the physicist John Tyndall, whom he met at George Eliot’s house in 1871. Tyndall may have told Abbott about the work of Hermann von Helmholtz, who gave public lectures on non-Euclidean geometry using the image of an imaginary two-dimensional creature living on a mathematical surface. Another likely source is the outrageous Charles Howard Hinton, who wrote his own book about a two-dimensional world in his 1907 An Episode of Flatland: How a Plane Folk Discovered the Third Dimension.

Abbott’s mathematico-literary legacy is a series of Flatland spin-offs: Dionys Burger’s Sphereland, Rudy Rucker’s short story ‘Message Found in a Copy of Flatland’ and his novel The Fourth Dimension, Alexander Keewatin Dewdney’s The Planiverse, and my own Flatterland. But what he was really trying to tell his readers was more subtle. Just as a humble square can transcend his plane world and aspire to the Third Dimension, so the women and the lower classes of Victorian England could transcend the confines of their stratified society and aspire to a higher plane of existence. More than 120 years later, it is a message that has lost none of its urgency.

Ian Stewart is Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at the University of Warwick and the author of numerous popular mathematics books, including Flatterland and The Annotated Flatland. His most recent book is Mathematics of Life.

Links to Works

Flatland : a romance of many dimensions (1884) by Edwin Abbott Abbott

An Episode of Flatland: How a Plane Folk Discovered the Third Dimension (1907) by Charles Howard Hinton