Only once has a British Prime Minister been assassinated. Two hundred years ago, on the 11th May 1812, John Bellingham shot dead the Rt. Hon. Spencer Perceval as he entered the House of Commons. David C. Hanrahan tells the story.

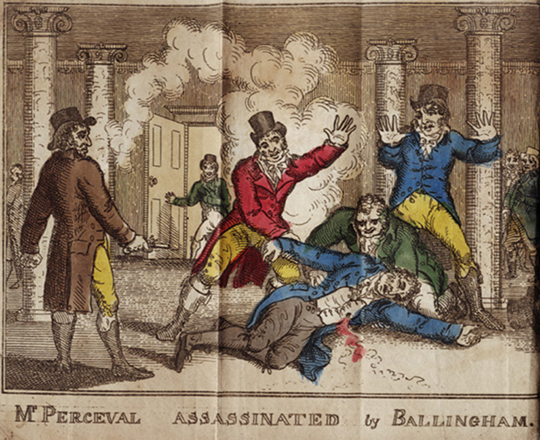

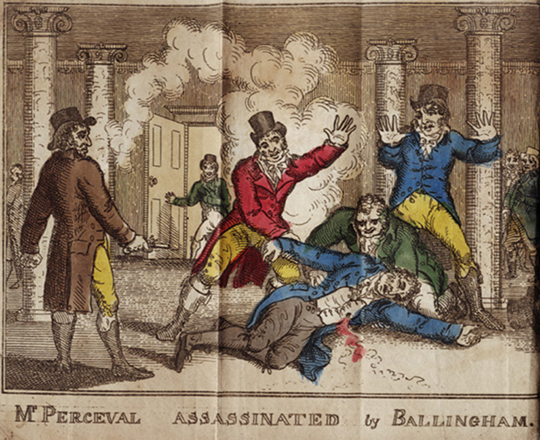

Illustration of the shooting, artist unknown. (Source: Norris Museum)

On Monday 11 May, 1812, an unremarkable, anonymous man, just over forty years of age, made his way to the Houses of Parliament. The man had become a frequent visitor there over the previous few weeks, sitting in the gallery of the House of Commons and carefully examining the various members of the government through his opera glasses. At 5.00 p.m. on this particular day he walked into the lobby that led to the House of Commons and sat near the fireplace. No-one could have known that he was carrying, concealed on his person, two loaded pistols.

As it was a fine evening Mr. Spencer Perceval, the Tory First Lord of the Treasury, or Prime Minister, had decided to dispense with his carriage and walk from No. 10, Downing Street, to the Houses of Parliament. He arrived there around 5.15pm, entered the building and walked down the corridor towards the lobby entrance to the House of Commons. He handed his coat to the officer positioned outside the doors to the lobby.

As Mr. Perceval entered the lobby a number of people were gathered around in conversation as was the usual practice. Most turned to look at him as he came through the doorway. No-one noticed as the quiet man stood up from beside the fire place, removing a pistol from his inner pocket as he did so. Neither did anyone notice as the man walked calmly towards the Prime Minister. When he was close enough, without saying a word, the man fired his pistol directly at Mr. Perceval’s chest. The Prime Minister staggered forward before falling to the ground, calling out as he did so words that witnesses later recalled in different ways as: “I am murdered!” or ‘Murder, Murder’ or ‘Oh God!’ or ‘Oh my God!’

Amid the confusion, a number of people raised Mr. Perceval from the ground and carried him into the nearby Speaker’s apartments. They placed him in a sitting position on a table, supporting him on either side. Most ominously, the Prime Minister had not uttered a single word since falling on the floor of the lobby, and the only noises to have emanated from him since had been a few pathetic sobs. After a short time Mr. Smith MP, on failing to find any perceptible sign of a pulse, announced his terrible conclusion to the group of stunned onlookers that the Prime Minister was dead.

The Assassination of Spencer Perceval, illustration by Walter Stanley Paget (1861-1908) from Cassell's Illustrated History of England. Vol.5 (1909)

Before long Mr. William Lynn, a surgeon situated at No. 15 Great George Street, arrived on the scene and confirmed that Mr. Smith was indeed correct. The surgeon noted the blood all over the deceased Prime Minister’s coat and white waistcoat. His examination of the body revealed a wound on the left side of the chest over the fourth rib. It was obvious that a rather large pistol ball had entered there. Mr. Lynn probed an instrument into the wound and found that it went downwards and inwards towards the heart. The wound was more than three inches deep. The Prime Minister, who was not yet fifty years of age, left behind a widow, Jane, and twelve children.

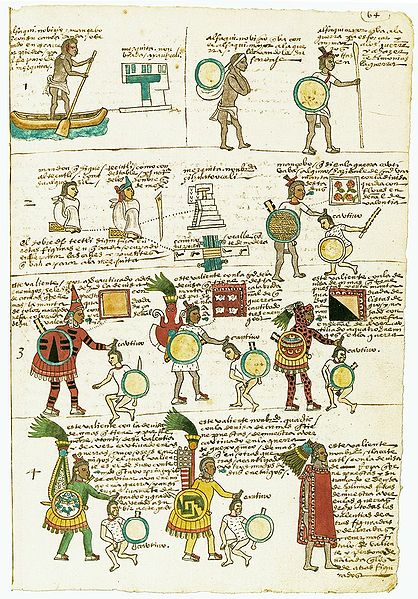

In the shock of what had happened, the assassin was almost forgotten. The man had not attempted to escape as he might well have done amid the confusion. Instead, he had returned quietly to his seat beside the fireplace. The identity of the man was revealed as John Bellingham, not a violent radical but a businessman from Liverpool. The details of his story soon began to emerge. As a result of a dispute with some Russian Businessmen, Bellingham had been imprisoned in Russia in 1804 accused of owing a debt. He had been held in various prisons there for the next 5 years. Throughout all of this time he had pleaded with the British authorities for assistance in fighting his cause for justice. He believed that they had not given his case sufficient attention.

Bellingham was finally released from gaol and returned to England in 1809 a very bitter man. He felt deep resentment against the British authorities and immediately set about seeking financial compensation from them for his suffering and loss of business. Once again, however, Bellingham felt that he was being ignored. He petitioned the Foreign Secretary, the Treasury, the Privy Council, the Prime Minister, even the Prince Regent, but all to no avail. No one was willing to hear his case for compensation. Finally, he came to the insane decision that the only way for him to get a hearing in court was to shoot the Prime Minister.

Detail from a painting of The Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, in the year of his death, 1812, by George Francis Joseph. (Source: National Portrait Gallery)

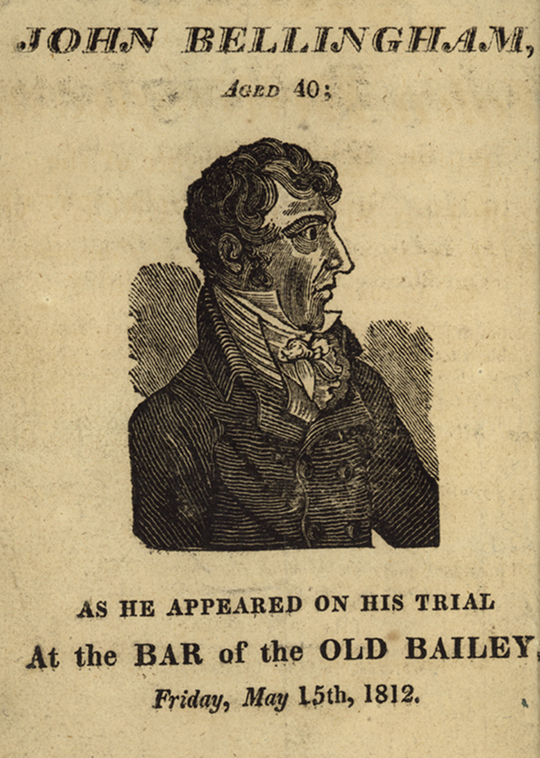

On the Friday following the assassination of the Prime Minister, John Bellingham did indeed get his day in court, but only to answer a charge of murder. His trial took place in a packed court room at the Old Bailey, presided over by Sir James Mansfield, the Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas. The tall, thin Bellingham came before the court wearing dark nankeen trousers, a yellow waistcoat with black stripes and a brown greatcoat. The members of his defence team first attempted to get the trial postponed on the grounds that they had not been given sufficient time to prepare for the case. Mr. Peter Alley, Bellingham’s chief counsel, told the court that he had only been given the case the day before and that he had never even met Mr. Bellingham until that very day. He asserted that given adequate time, in particular to find medical experts and witnesses in Liverpool who knew Mr. Bellingham personally, he was confident he could prove his client to be insane. The Attorney General, Sir Vicary Gibbs, on behalf of the prosecution, argued vehemently against any such postponement. Ultimately Mr. Allen’s request was unsuccessful and the trial proceeded.

The Attorney General set about dismantling the reason Bellingham had given as justification for his heinous act by arguing that the Government had been aware of what had happened to him in Russia, had examined his claims and had rejected them. He also rejected any notion that Bellingham was insane. He said that Bellingham had been well able to conduct his business and had been trusted by other to conduct theirs without any hint of insanity on his behalf.

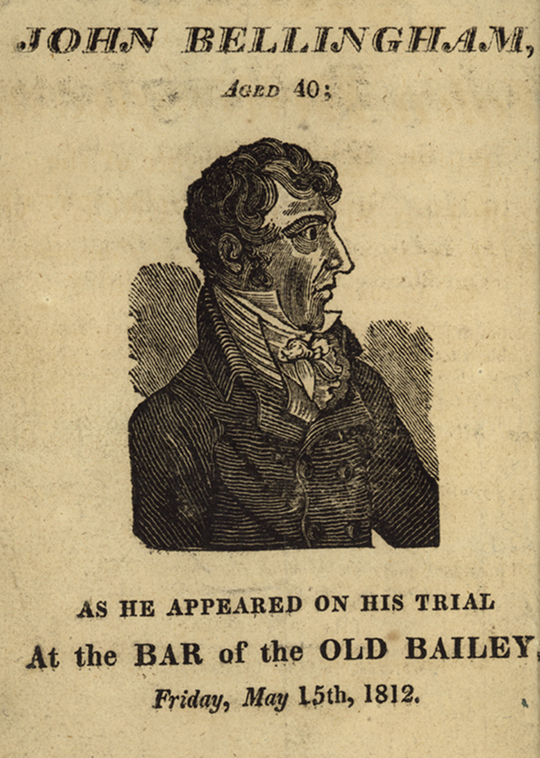

Titlepage from the pamphlet 'The Trial of John Bellingham for the Wilful murder of the Right Hon. Spencer Perceval, in the lobby of the House of Commons' (Source: National Library of Medicine)

When his time came to speak, Bellingham continued to base his defence upon what had happened to him in Russia: his unjust arrest for a debt he did not owe and the failure of the British Government to assist at that time and since. Before outlining the details of his experience in Russia, he stated that he was pleased the judge had not accepted his counsel’s arguments alleging his insanity. He made it clear that although he believed what he had done to be necessary and justified, he bore Mr. Perceval or his family no personal malice:

Gentlemen, as to the lamentable catastrophe for which I am now on my trial before this court, if I am the man that I am supposed to be, to go and deliberately shoot Mr. Perceval without malice, I should consider myself a monster, and not fit to live in this world or the next. The learned Attorney General has candidly stated to you, that till this fatal time of this catastrophe, which I heartily regret, no man more so, not even one of the family of Mr. Perceval, I had no personal or premeditated malice towards that gentleman; the unfortunate lot had fallen upon him as the leading member of that administration which had repeatedly refused me any reparation for the unparalleled injuries I had sustained in Russia for eight years with the cognizance and sanction of the minister of the country at the court of St. Petersburg.

Bellingham was clear about where he felt the blame lay for Spencer Perceval’s death:

A refusal of justice was the sole cause of this fatal catastrophe; his Majesty’s ministers have now to reflect upon their conduct for what has happened. . . . Mr. Perceval has unfortunately fallen the victim of my desperate resolution. No man, I am sure, laments the calamitous event more than I do.

In the end, of course, his arguments for justification had no influence upon a judge and jury shocked by his horrific murder of the Prime Minister. The Lord Chief Justice even became openly emotional and began to cry at one point during his statement to the jury:

Gentlemen of the jury, you are now to try an indictment which charges the prisoner at the bar with the wilful murder . . . of Mr. Spencer Perceval, . . . who was murdered with a pistol loaded with a bullet; . . . a man so dear, and so revered as that of Mr. Spencer Perceval, I find it difficult to suppress my feelings.

He dismissed any idea that Bellingham might have been insane at the time of committing the crime:

. . . there was no proof adduced to show that his understanding was so deranged, as not to enable him to know that murder was a crime. On the contrary, the testimony adduced in his defence, has most distinctly proved, from a description of his general demeanour, that he was in every respect a full and competent judge of all his actions.

In such circumstances it is no surprise that John Bellingham was found guilty of Spencer Perceval’s murder by a jury that took only fourteen minutes to reach a verdict. On the following Monday he was executed and his body sent for dissection to St. Bartholomew’s hospital. He is remembered in history as the only assassin ever of a British Prime Minister.

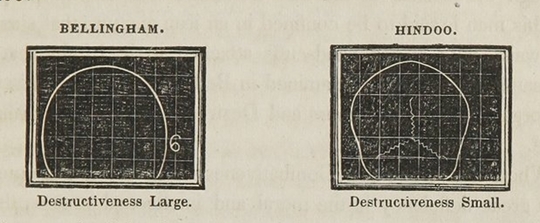

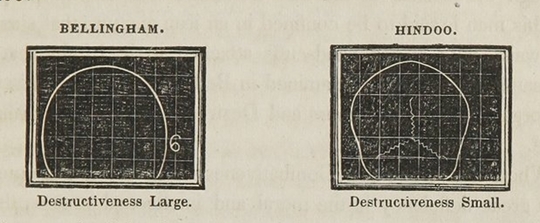

Following his execution John Bellingham's skull became the subject of research for phrenologists, representing the head of a destructive personality. Shown here is a comparison of Bellingham's skull with that of a 'Hindoo', from A System of Phrenology (1834) by George Combe

David C. Hanrahan is the author of The Assassination of the Prime Minister: John Bellingham and the Murder of Spencer Perceval (The History Press, 2008). His other books include: Colonel Blood: The Man Who Stole the Crown Jewels

(The History Press, 2008). His other books include: Colonel Blood: The Man Who Stole the Crown Jewels (The History Press 2003); Charles II and the Duke of Buckingham

(The History Press 2003); Charles II and the Duke of Buckingham (The History Press 2006); The First Great Train Robbery

(The History Press 2006); The First Great Train Robbery (Robert Hale, 2011).

(Robert Hale, 2011).

Links to Works

Transcript of the Old Bailey trial of John Bellingham

The Substance of a Conversation with John Bellingham, the assassin of the late Right Hon. Spencer Perceval (1812), by Daniel Wilson

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!