This is just an automatic copy of Public Domain Review blog.

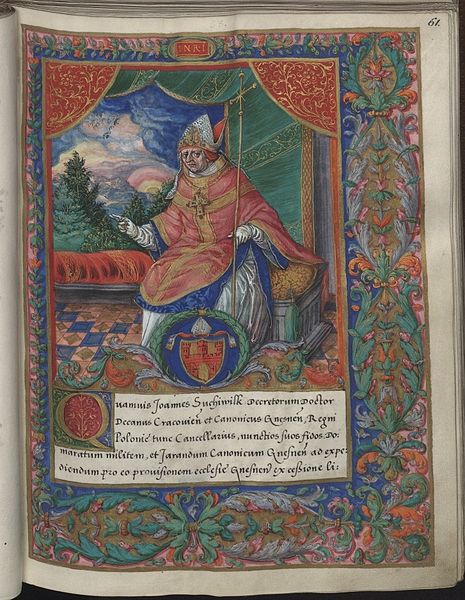

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2012/01/12/a-catalogue-of-polish-bishops/

In 2011 many countries around the world welcomed The Wonderful Adventures of Nils and the other works of the Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf into the public domain. Jenny Watson looks at the importance of Lagerlöf’s oeuvre and the complex depths beneath her seemingly simple tales and public persona.

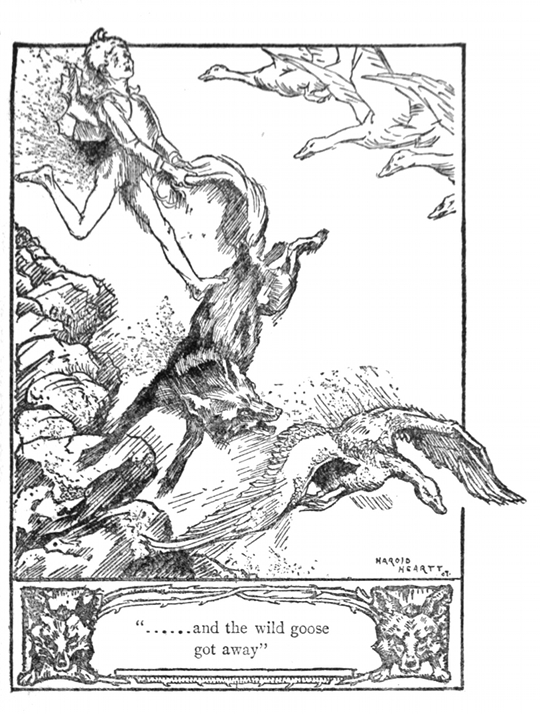

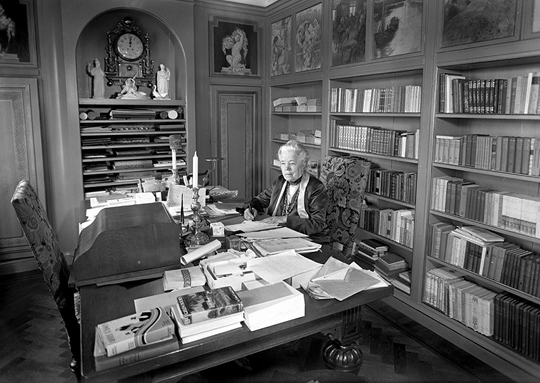

Lagerlöf circa 1900

In 1909, an ageing “spinster,” with a marked limp, stood in the Grand Hotel in Stockholm. That woman was Selma Lagerlöf, the first woman and the first Swede to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. She stood in front of a large audience, which included the King and Queen of Sweden, and delivered her Nobel Prize Banquet Speech, a speech which to many epitomized who she was, a charming and humble sagotant, a quaint, sweet storyteller aunt, who received her inspiration from Wermland and in particular, her father.

Lagerlöf opened her speech by explaining that she had been nervous coming up to Stockholm to receive the prize, that her previous trips to Stockholm had been to do something “difficult,” such as take examinations or try to find a publisher for her work, never to be celebrated. Moreover, in the past few months she had lived in solitude and had become shy. She dispelled her anxiety, though, by thinking of those who would be happy for her. This was when she had thought of her father and wished that he were still alive to see the moment. Almost imperceptibly, Lagerlöf glides into storytelling, creating a scene in which she imagines visiting her father in Paradise and telling him she is in debt and needs his help. It eventually becomes clear that this debt is what she owes to those who have contributed to and supported her as a writer: the vagabonds who gave her stories to tell through their actions, the Swedish language and those who taught it to her, the great authors of Sweden, her readers and most of all the Academy which has placed its trust in her. In true Lagerlöf fashion, she humbly deflected the recognition she deserved for the Nobel Prize, and at the same time ― through a charming story ― demonstrated her storytelling sagotant abilities and her devotion to her father.

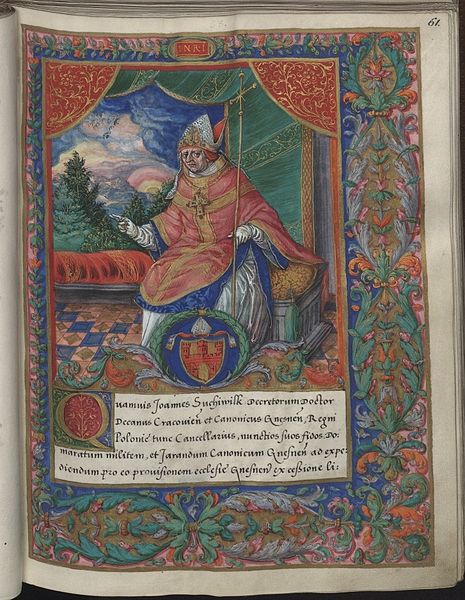

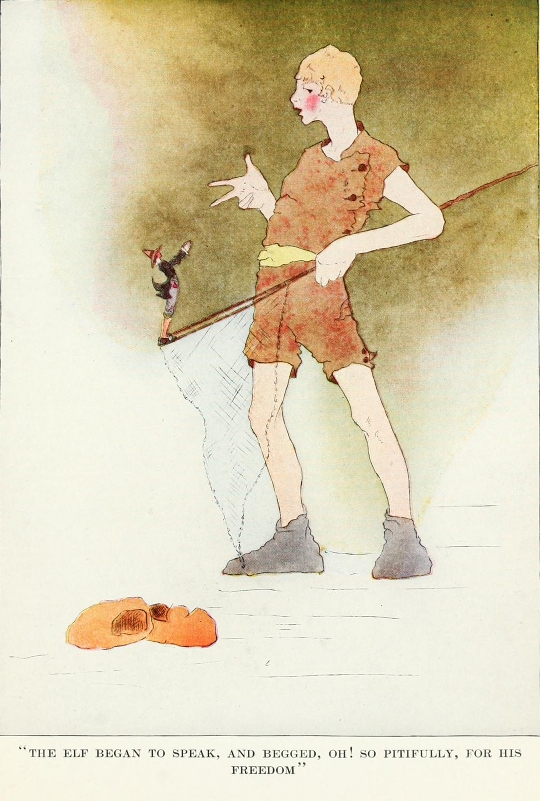

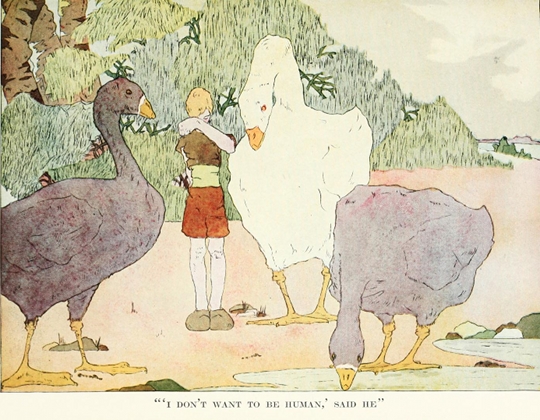

Illustration by Harold Heartt from the 1907 English translation of The Wonderful Adventures of Nils

In a less flattering light, the contemporary Swedish writer, P.O. Enquist, has interpreted Lagerlöf’s speech as a reflection of Lagerlöf’s co-dependence on an alcoholic father. No doubt, Lagerlöf’s father was an alcoholic, something on which Lagerlöf did not concentrate in her later fictional memoirs (Mårbacka and A Child’s Memories). Nor did she concentrate on the fact that her father was completely against her furthering her education; and in direct defiance of his wishes, she did so anyway. Instead, she highlighted the father who sang songs, brought laughter to the family and had dreams for the family home, Mårbacka. Does this indicate repression and co-dependence, as Enquist argues? Perhaps.

More likely, however, and better supported by her life and works, is that Lagerlöf was a multi-faceted woman who understood the difference between surface and content. Lagerlöf entered the world of writing with few female role models, a strong desire to make her mark on the world and the recognition that it would be men who would make or break her career.

And she was correct. Lagerlöf’s first literary attempts were at the age of fifteen, but her breakthrough came in the late 1880s when she finally gained the courage to write the work she wanted to, Gösta Berlings Saga (1891) ― an epic novel that contradicted the Naturalist tendencies of the time. In 1890 she sent the first five chapters to Idun magazine’s literary contest and won. Following this recognition, the full manuscript was published by Fritiof Hellberg in Stockholm. Although the work was well received by her fellow Wermlander, Gustaf Fröding (also a distant relative to Lagerlöf), most literary critics who took notice were not so enthusiastic, claiming that the narration was “strange,” the style “unnatural,” and the structure “rather loose.” These aspects, however, were exactly what the internationally renowned literary critic, Georg Brandes, would praise in 1893, when he reviewed the book for the first time. He found the presentation of material “original,” and praised the “narrative’s rhythmically fluid, often quite simply lyric style.”

Lagerlöf in her workroom at home in the residence Mårbacka.

With these words and the following attention from other critics, Lagerlöf’s career was launched. Interestingly, Lagerlöf had originally named her work “Gösta Berling,” but the publisher of the first edition, in order to strengthen the title, added saga, which means a story in terms of an Icelandic saga or a fairy tale. Critics quickly jumped on the fairy tale definition. This, along with Brandes’ random thoughts about the author while he critiqued her first novel – that is, that Lagerlöf was no doubt a “maiden lady” whose “warm, living imagination is like a child’s” – led to the image of Lagerlöf as a naïve, kind spinster who told simple stories from her homeland. Lagerlöf did not fight the image of herself, mainly because her audience liked it and it increased her popularity.

Many of the works she wrote in her lifetime – on the surface – appeared to support this image; to name a few: The Queen of Kungahälla and Other Sketches from a Swedish Homestead (1899), Jersualem I (1901), Herr Arnes Hoard (1903), The Girl from the Marshcroft (1908), They Soul Shall Bear Witness (1912), and The Ring Trilogy (1925-1928). However, it is perhaps her most internationally famous work, The Wonderful Adventure of Nils, published in 1906-7, that cemented the image, both at home and abroad. Lagerlöf was commissioned by the National Teachers Association in 1902 to write a geography reader for the Swedish public schools. She spent three years learning about the landscape, animals and plant life, industry and folk life of Sweden and then interwove these facts into the story of Nils Holgersson, a young boy who is punished for his bad behavior by the farm tomte. He is shrunken to a small size. In this form, he is able to talk and understand the animals around him and he ends up flying across Sweden on the back of a goose. During the trip, the reader learns about each province and the geography of Sweden.

Illustrations by Mary Hamilton Fry featured in the 1913 English translation edition of The Wonderful Adventures of Nils

The Wonderful Adventures of Nils was an instantaneous success, not only in the public schools and Sweden, but across the world. Indeed, still today it is probably her most famous work. Nils Holgersson appears on the back of the Swedish 20 crown note (Lagerlöf is on the front), and from Germany to Russia to Japan, Nils Holgersson can be found in bookstores (and on TV).

Yet, Lagerlöf was in no way a simple sagotant from Sweden ― not in her works and not in her life. Lagerlöf did not only tell stories of Sweden. For example, The Miracles of Antichrist (1897) was a novel set in Italy, centering on the moral conflict between Socialism and Christianity; Jerusalem II (1902) takes place in Palestine; and The Outcast (1918) was a pacifist novel in reaction to World War I. On the surface, most of Lagerlöf’s works can be read at face value and they are indeed enjoyable. However, even as can be seen in her public school reader, there are numerous layers beneath the surface―layers which are thought out and constructed (e.g. the pedagogy behind Nils Holgersson). Lagerlöf’s novels and stories explore human psychology ―the psychological layers of murder, love, jealousy, war, greed, religion. Her work, Herr Arnes Hoard, is a good example of such a story– a ghost story which is thrilling to read, but which, if one understands the ghost as human conscience, is an in depth study of guilt and love.

Detail from an A. Blomberg photograph of Lagerlöf taken in 1906

Lagerlöf’s life had a similar dynamic between surface and depth. On the surface (as she herself portrayed in her autobiographical fiction, Mårbacka I and II (1922, 1930) and The Diary of Selma Lagerlöf (1932), she was a simple girl from Wermland, a devoted and subservient daughter, a woman who became a spinster due to her limp, and a storyteller indebted to her country. Yet, beneath the surface, she was an exceptionally well-read woman who clearly drew from the classic literature of the Western world. She was a woman of strong will―defying her father who did not want her to continue her education and a strong voice in the woman’s movement in Sweden. Although she was a spinster in the “traditional” sense, she was involved with at least one woman, Warburg Olander, if not more. Finally, although she was clearly indebted to her country for many stories, she did not simply retell them. She created new masterpieces in the Swedish language, in-depth studies of human nature and psychology. She created literature worthy of the Nobel Prize. And even upon receiving the Nobel Prize, she continued the image of herself. Lagerlöf spun stories, whether they were about others or herself – incredible stories, with fascinating depths.

Jenny Watson is the associate dean of the Humanities and an associate professor of German and Scandinavian Literature at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She received her Masters and PhD at the Univeristy of Illinois/ Champaign-Urbana, with a double concentration in German and Scandinavian literature. She is author of the book, Selma Lagerlöf och Tyskland (Selma Lagerlof and Germany), published by the Lagerlöf society, as well as numerous articles and presentations about Lagerlöf. Her present research project is an English-language biography of Selma Lagerlöf.

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2012/01/11/selma-lagerlof-surface-and-depth/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/24/the-night-before-christmas-1905/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/23/santa-claus-proves-there-is-a-santa-claus-1925/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/22/yuletide-entertainments/

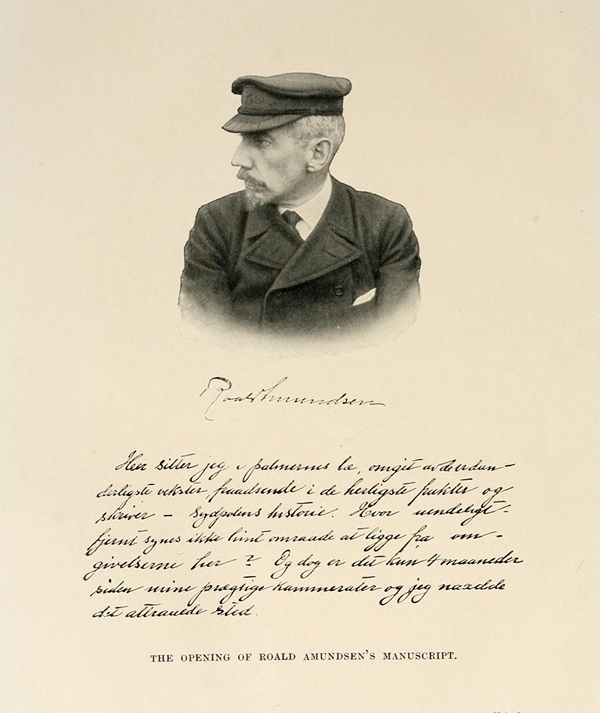

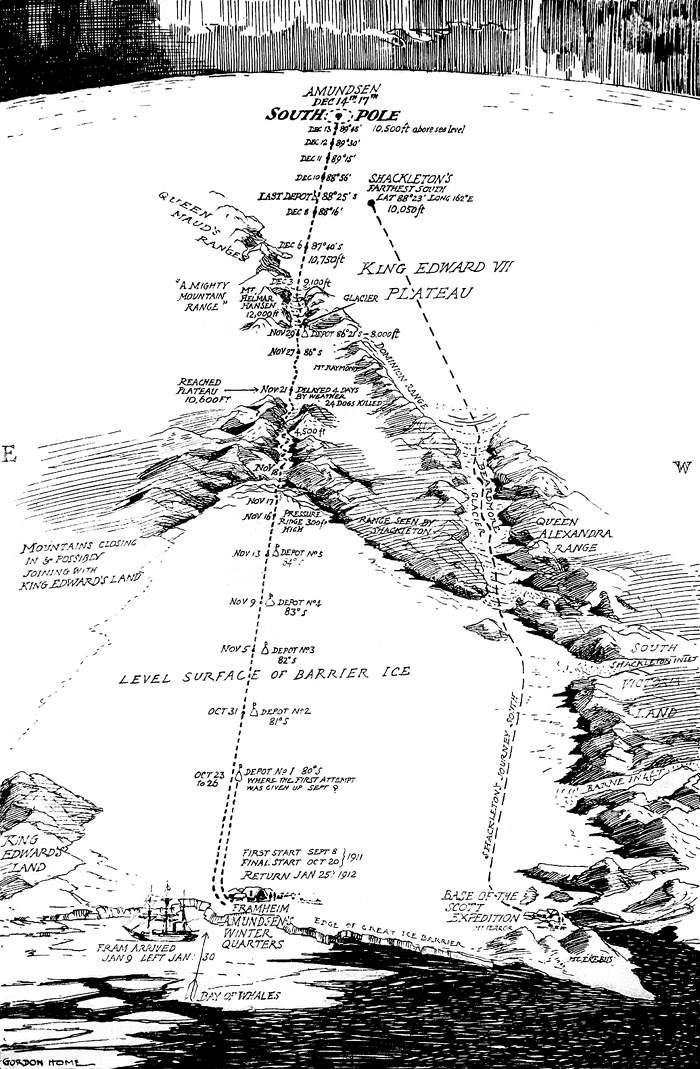

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/14/amundsens-south-pole-expedition/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/13/the-voice-of-florence-nightingale/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/08/the-daddy-long-legs-of-brighton/

As well as being poet laureate for 30 years and a prolific writer of letters, Robert Southey was an avid recorder of his dreams. W.A. Speck, author of Robert Southey: Entire Man of Letters, explores the poet’s dream diary and the importance of dreams in his work.

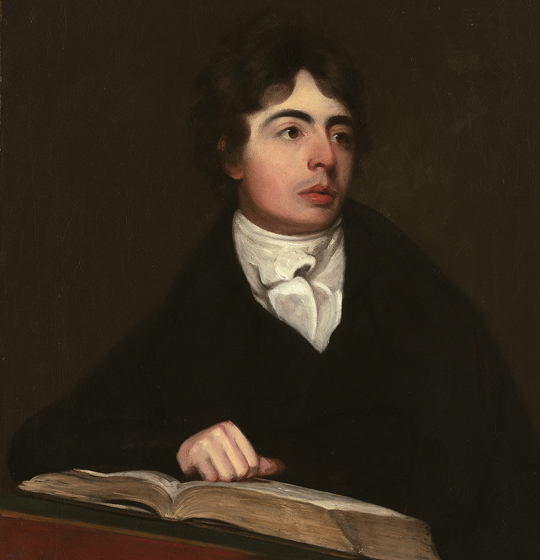

Detail of a portrait of Southey painted by John James Masquerier in 1800.

Robert Southey (1774 – 1843), the poet laureate, biographer, historian and, in Byron’s words, ‘entire man of letters’ used a note book to record many of his dreams. A celebrated line in his verse was ‘my days among the dead are past’, referring to the works by authors who had died, many of them centuries ago, which lined the walls of Greta Hall, Southey’s home in Keswick. An analysis of his dreams demonstrates that his nights were passed among them too, since a disproportionate number of those which he recorded dealt with the dead. Deceased relatives and friends frequently visited him in them. He also encountered dead authors, as in the dream he had on 7 January 1805. ‘I was supping at Garrick’s house, and seated at his left hand, at the top of the table; my memory had made up his face accurately; he got upon the table, and spoke an epilogue of his own writing in the character of a cook –maid, and promised, at Mrs Garrick’s desire, to recite a serious poem afterwards, that I might hear him’. In another dream he was ‘at Swift’s house in Dublin, where he was living with two sisters’. And in another he met Matthew Lewis, the author of a sensational Gothic novel, The Monk. ‘Monk Lewis’ had been a contemporary of Southey’s at Westminster school, though he confessed that he never ‘had any affection for the man.’ This, however, did not prevent him contributing to a volume edited by Lewis, Tales of Wonder. Southey’s contribution consisted of six poems, all of which contained Gothic elements, including dreams. Thus ‘Bishop Bruno’ wakes from a recurrent dream that he had rung his own death knell, only to discover that it was prophetic. ‘Lord William’ drowns young Edmund, his deceased elder brother’s son, to claim the house of Erlingford, only to find that

In vain at midnight’s silent hour

Sleep closed the murderer’s eyes

In every dream the murderer saw

Young Edmund’s form arise.

‘The Pious Painter’ was renowned for his realistic portrayals of the Devil

What the Painter so earnestly thought on by day

He sometimes would dream of by night.

Southey himself strongly believed that waking thoughts led on to dreams. It led him to organise his days so that he did not work on one topic all day but switched from one to another, from composing poems to reviewing books to writing letters. This routine was not only economical in its use of time but was ‘also essential to the preservation of my health; for, by long experience, I know that whenever my attention is devoted to one object my sleep is disturbed by perplexing dreams concerning it. The remedy is easy; I do one thing in the morning, another in the evening – I never dream of either’.

This routine was not foolproof, however, for his dream book records that what had occupied his mind during the day often inspired dreams that same night. The entry for 4 December 1821, for instance, describes a dream in which ‘Palmerin of England gave me Arcalaus, the enchanter, in the shape of an egg, the enchanter having taken that form, and bade me deliver it to Urganda. Urganda took the egg, and said her husband should eat it for his supper’. Southey then added to his account that his daughter ‘Isabel had been reading Amadis and Palmerin, and talking to me a great deal about both; hence this jumbled dream.’

Detail from The Knight's Dream (1655) by Antonio de Pereda (1611–1678)

Southey did not record all his dreams in the book by any means, he selected only those which he considered to be significant. As we have seen his poetry also alluded to dreamers and dreaming. The best source, however, for his reflections on his dreams is his 7000 or so extant letters. Unfortunately few of these have been published in reliable scholarly editions, most being scattered throughout repositories in Britain and North America. However, under the general editorship of Lynda Pratt, Tim Fulford and Ian Packer these are now being published electronically as The Collected Letters of Robert Southey. When the edition is complete it will be possible to trawl through it, for being on line the letters can be searched, for example for dreams. A search for ‘dream’, ‘dreamer’ and ‘dreaming’ brought up several passages in Southey’s correspondence in which dreams are mentioned. Some show the same morbid interest in death and ghosts that his dream book documents. Thus on 20 October 1793 he wrote to Horace Walpole Bedford:

I’ll betake me to bed & look sharp for a dream.

God of dreams hear my prayer To my pillow repair

Indulge my petition tonight

Around my wild brain

Send thy fanciful train

And give me a dream I may write

And later:

… bid thy sprightly phantoms rare

Round my sleeping head repair.

Let me see in church yard gloom

The ghost slow rising from the tomb

Slow & stern his pale hand wave

And bid me follow to the grave.

Three weeks later, in mid November, he wrote to Horace’s brother, his old school friend Grosvenor Charles Bedford: ‘I am going to bed … to dream of you & heaven & happiness unless the demon of dismal dreams pops up under my pillow & harrows up my heart with some of his chimeras – oh if life were all one agreeable dream – or rather if death were – would there be a crime in taking laudanum as an opiate? Good night.’

W. A. Speck is author of Robert Southey: Entire Man of Letters (Yale University Press, 2006) and ‘His nights amont the dead were passed: Robert Southey’s dreams’ in Robert Southey and the Contexts of English Romanticism edited by Lynda Pratt (Ashgate, 2006).

See also Robert Southey on Wikisource

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/05/robert-southey%e2%80%99s-dreams-revisited/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/12/04/stella-maris-1918/