(Images and text courtesy of The National Media Museum via Flickr)

This is just an automatic copy of Public Domain Review blog.

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/11/10/kodak-no-1-circular-snapshots/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/11/08/your-name-here-1960/

Lucy Worsley, Chief Curator at Historic Royal Palaces and author of Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court, on the strange case of the feral child found in the woods in northern Germany and brought to live in the court of George I.

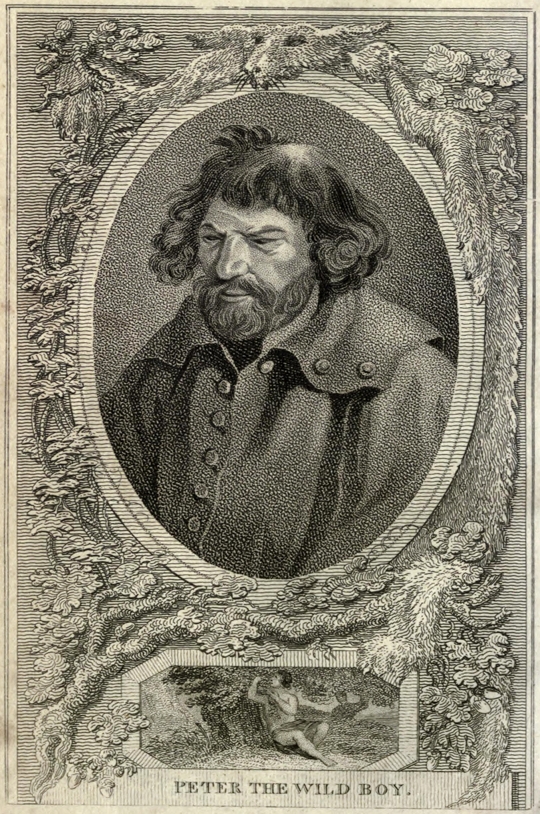

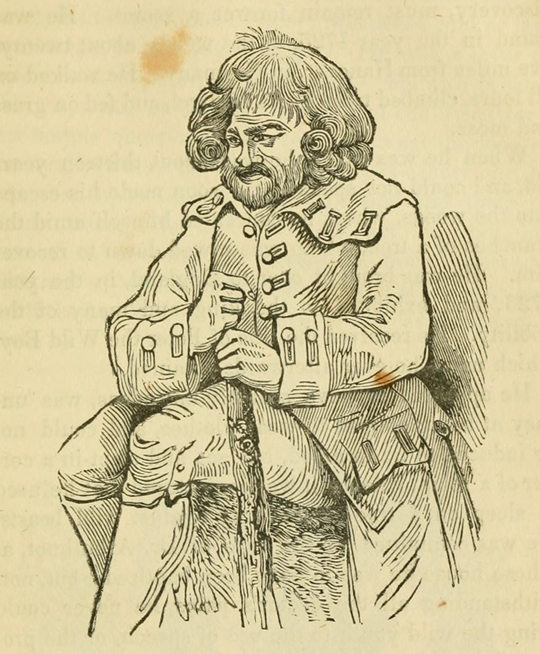

Illustration from The Eccentric Mirror (1807) by G.H. Wilson

On the evening of 7 April 1726, George I’s courtiers crammed themselves into the drawing room at St James’s Palace. The room buzzed with their trivial chatter about balls and masquerades, everything seemed just as usual.

But a sensational event would make this particular palace party the most memorable in years. The doors opened to reveal a brace of footmen, bearing between them a grinning, bushy-haired boy. He was perhaps twelve years old.

There was something decidedly odd about this youth. For a start, he seemed not the least ‘embarrassed at finding himself in the midst of such a fashionable assembly’. Once lowered to the floor, he scuttled about using his arms, like a chimp, and scampered right up to the king. The courtiers were scandalised by his audacious lack of ceremony.

This was their first encounter with Peter, the curious ‘Wild Boy’. Green-eyed, with strong teeth, he had ‘a roving look’ in his eyes. He often giggled, and lacked the solemn and stately demeanour of the other courtiers. Strangest of all, he could not speak.

Everyone shared his delight when he heard a watch striking the hour for the first time, and Peter’s comical ways provided much amusement. But he also sparked off engrossing philosophical debates. His very existence raised the fascinating question of what it really meant to be human.

Peter’s unlikely journey to court began in the German forest of Hertswold. In 1725, local forest folk had come across a feral child, ‘naked and wild’. He’d been living all alone in the woods, eating nuts and acorns.

There was a general assumption that the Wild Boy was ‘rescued’ from the wilderness, but the more detailed accounts of his capture reveal that he was actually hunted down. He took refuge up a tree, which had to be felled before he could be caught. His captors didn’t know quite what to do with him, so they thrust him into the local ‘House of Correction’.

But news of Peter and his bizarre, speechless condition reached the nearby palace of Herrenhausen, the summer home of the German-born George I. The king ordered Peter to be brought from the prison to the palace, made him a member of his household, and took him back to London.

Peter the Wild Boy and Dr Arbuthnot painted by William Kent, at Kensington Palace - courtesy of Historic Royal Palaces (NB: not published under an open license).

Now the Wild Boy became a kind of court pet. Soon after his arrival, he was taken to Kensington Palace to sit for William Kent, the painter who was decorating the King’s Grand Staircase there with portraits of the king’s favourite servants. Peter’s painting still remains there today.

The courtiers were entranced by Peter, and a mania for the Wild Boy took off outside the palace gates as well. Londoners crowded to see the waxwork of Peter which appeared in Mrs Salmon’s celebrated gallery in the Strand. Writers hailed him as ‘the most wonderful wonder’, and ‘one of the greatest curiosities of the world since the time of Adam’.

Throughout the centuries, feral children like Peter have aroused feelings of mingled pity and fear. More seriously, Peter fascinated the intellectuals then exploring the questions raised by the Enlightenment. Philosophers were beginning to assert the primacy of reason over superstition. They even debated the very definition of a human being, and whether or not people had souls. Peter proved to be a stimulating test case. If he possessed no speech, did he therefore possess no soul? Was he really just an animal? Or was he an admirable and ‘noble savage’, who’d lived a life untainted by society? Jonathan Swift remarked that the subject of the Wild Boy had been ‘half our talk this fortnight’, and Daniel Defoe thought he was the most interesting thing in the world.

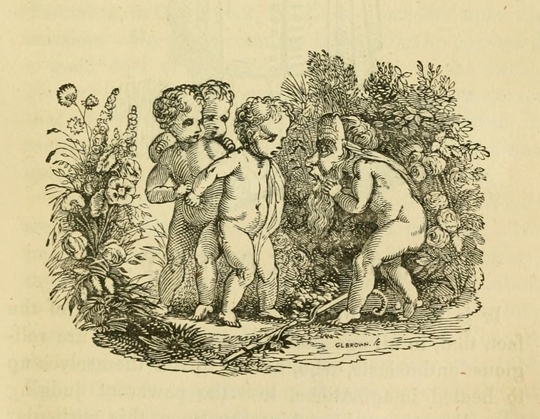

Illustration from Curiosities of Human Nature (1843) by Samuel G. Goodrich.

The Wild Boy became wonderful fodder for the city’s satirists. The few accurate facts about his life were soon forgotten or distorted in a deluge of pamphlets now printed about him. Ostensibly about Peter himself, their writers were really using him to mock the court, the courtiers, and even the whole silly race of men. The Wild Boy’s lack of worldly knowledge exposed the shallow foundations upon which fashionable society was built. London’s satirists invented more and more ludicrous transgressions that Peter was said to have committed: he licked people’s hands in greeting; he wore a hat in the king’s presence; he’d stolen the Lord Chamberlain’s staff.

Daniel Defoe joined in with his own wild cadenza of speculation. It would be a terrible indictment of the present age, Defoe argued, if the Wild Boy had actively chosen his previous way of life, to ‘converse with the quadrupeds of the forest, and retire from human society’. He was really suggesting that Peter was in fact the only truly sensible person alive.

Back at the palace, the Wild Boy soon began to show signs of distress. The first time he saw someone removing stockings, he was ‘in great pain’, thinking the man was peeling the very skin from his leg. The courtiers had enormous trouble in getting Peter into a new green suit. As well as the daily struggle over his clothes, Peter could not be made ‘to lie down on a bed, but sits and sleeps in a corner of the room’. These details of a little boy bewildered pierce the heart.

Illustration from Curiosities of Human Nature (1843) by Samuel G. Goodrich.

Peter’s tight court coat, cut much more restrictively than a modern jacket, prevented him from ‘crawling or scrambling about’, and he learned to walk. Eighteenth-century court garments were designed to make the wearer stand with shoulders lowered, chest puffed, and toes turned-out. They began to do their work upon the Wild Boy’s posture.

Eventually he grew used to his fine clothes. He also learned to pick pockets, from the most innocent of motives: ‘if he finds nuts or fruits, he is very glad of them’. This was charming and amusing. But when Peter stepped over the invisible line that defined acceptable behaviour, he was beaten on the legs with a ‘broad leather strap to keep him in awe’.

George I, exasperated by Peter’s wild ways, put him under the care of the medical doctor John Arbuthnot to be taught to speak ‘and made a sociable creature’. Dr Arbuthnot is another of the figures depicted in William Kent’s staircase paintings at Kensington Palace. He gave Peter daily lessons, but progress was slow as the Wild Boy had ‘a natural tendency to get away if not held by his coat’.

Peter did indeed learn to ‘utter after his tutor words of one syllable’. But he would never really engage with other people through language. Dr Arbuthnot had Peter baptised nevertheless, just in case he did have a soul.

Illustration from Wonderful Characters (1821) by Henry Wilson.

Even with the advantage of hindsight, it’s not exactly clear what Peter’s condition was. It is likely that he was autistic, and it’s been argued that he had Pitt-Hopkins syndrome. This condition would explain his learning difficulties and the remarkable Cupid’s-bow shape to his upper lip. Perhaps Peter was abandoned in the woods in the first place by a mother who considered him damaged or defective.

Eventually the courtiers grew bored with him, and Peter was sent to live in retirement on Broadway Farm near Berkhamsted in Hertfordshire. There he lived a long and quiet life, remaining ‘exceedingly timid and gentle in his nature’, fond of gin, and of onions. He liked to watch a fire burn, and loved ‘to be out on a starry night’. In autumn he would still show ‘a strange fondness for stealing away into the woods’ to feed upon acorns.

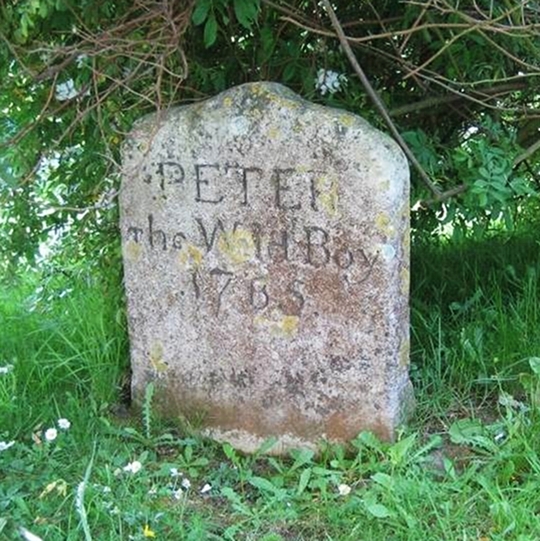

Peter constantly visited by the curious, including the novelist Maria Edgeworth, who commented that in old age he looked just like a bust of Socrates. He was in some measure loved by the farming families who looked after him. After the sudden death of his last carer, Farmer Brill, Peter ‘refused food, pined away, and died in a few days’. It was 22 February 1785.

I have visited his grave in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Northchurch, near Berkhamsted, which is often laid with flowers by an unknown person. When I asked a member of the congregation if she knew who places the bouquets, I was moved by her answer.

‘We’ve no idea who leaves the flowers’, she said, ‘but it must be someone who thinks that Peter should be remembered’. And so he should be.

Peter's grave in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Northchurch, near Berkhamsted.

Lucy Worsley is Chief Curator at the charity Historic Royal Palaces, which opens the unoccupied royal palaces of London including The Tower of London, Hampton Court and Kensington Palace to 3.2 million visitors a year. Her book Courtiers: The Secret History of the Georgian Court was published by Faber and Faber in 2011. She has also presented a BBC television series on the topic of her new book If Walls Could Talk, An Intimate History of the Home (Walker Books, 2012). Please visit her website.

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/11/07/peter-the-wild-boy/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/11/02/apollo-11-onboard-recordings/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/11/01/engravings-by-dominicus-custos/

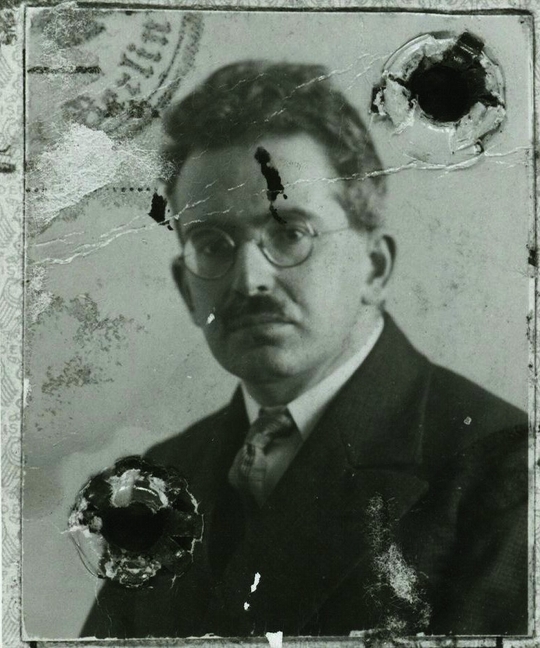

On the run from the Nazis in 1940, the philosopher, literary critic and essayist Walter Benjamin committed suicide in the Spanish border town of Portbou. In 2011, over 70 years later, his writings enter the public domain in many countries around the world. Anca Pusca, author of Walter Benjamin: The Aesthetics of Change, reflects on the relevance of Benjamin’s oeuvre in a digital age, and the implications of his work becoming freely available online.

Benjamin's passport photograph from 1928 - courtesy of the Walter Benjamin Archiv, Berlin.

Walter Benjamin, a German-Jewish intellectual of kaleidoscopic abilities and interests – literary critic, philosopher, translator, essayist, radio presenter – has always fascinated academics and intellectuals. His dense academic prose, his unique reading of Marxism, his fascination with Jewish mysticism, but more importantly, his ability to capture some of the major transformations of the early 19th century Europe in a series of literal and temporal frames that distilled the very material which gave it consistency – iron, concrete, shopping arcades, new technologies such as photography and film, ideological propaganda – into words, earned Benjamin a cult-like following which continues today. Artists, philosophers, theorists from every discipline, continue to offer different readings and meanings to his work, which remains strikingly relevant to social and political transformations today.

If Benjamin’s public is mainly of an academic nature today, that was certainly not the case at the time of his writing. With his habilitation rejected by the University of Frankfurt, Benjamin was forced to survive outside of academia, and hence to write accordingly: most of his work appears in fragments – essays, short stories, journal entries, letters, newspaper and journal articles, radio broadcasts – which mainly appeared in the public domain through his journalistic and radio work, with the exception of a few pieces intended for publication by the Institute for Social Research led by Horkheimer and Adorno. This significantly affected not only his writing style – making most of it much more accessible to a larger public – but also his thoughts on the role of language and text. The fragmentary nature of his work, initially a result of financial and practical constraints, later became a trademark of Benjamin’s methodology, particularly obvious in his unfinished magnus opus, the Arcades Project.

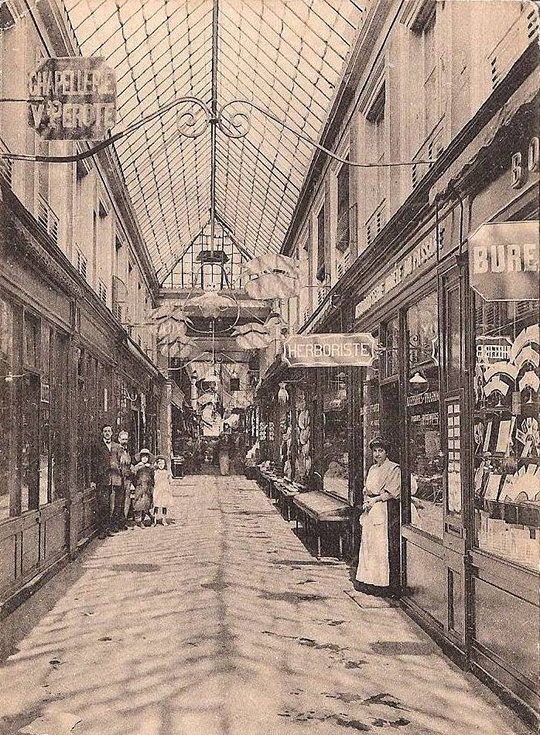

Detail from a 19th century postcard showing the Passage Bellivet, Caens, opened in 1836.

Conceived as a catalogue of thoughts and images on 19th century Paris as the emblematic modern city, the Arcades Project brings incredible innovation not only stylistically – through the fragmentary nature of the text, which could be read and accessed in non-linear fashion – but also intellectually, by breaking the traditional frame of text which rests upon a necessary temporal and linguistic progression, and effectively establishing a new architecture which relies less on words and more on the images and material that those words conjure. Benjamin effectively reconstructs different Parisian frames, capturing them not unlike a photographer captures a scene. Each of these frames, as fragments of text, contains its own temporality, existing both in relation to but also independent from the others. By embedding the relevance of each frame into a temporality that emerges directly from the material it depicts – for example, by depicting the old Parisian arcades in ruin as a new type of architecture emerges – Benjamin creates a unique dialectic in which the present can never exist as independent from either the past or the future.

The Galerie Vivienne during the Bourbon restauration : 8 rue Vivienne, Paris 2nd arr. c. 1820, one of the arcades mentioned in Benjamin's Arcades Project.

The return of Benjamin’s work back to its original wider audience, the public domain, at this particular point in time, creates a series of new possibilities that Benjamin himself could not have envisioned. Internet technology and the ability to collect, categorize and re-arrange Benjamin’s fragments in an electronic publication form could perhaps provide Benjamin with a post-humos solution to his struggle to organize the Arcades Project in a manner that would both appease publishers and maintain its innovative framework. One can already imagine the possibilities of a new interactive electronic Arcades Project in which Benjamin’s fragments could easily be navigated through the click of a button, the text appearing as a digital image, a material fragment much closer to Benjamin’s original intentionality.

Benjamin’s obsession with sorting, filing, keeping tabs on his work, making copies of manuscripts to leave with different friends, carrying a copy of the unfinished manuscript of the Arcades Project with him to his death, as he attempted to escape Nazi-occupied France, shows his determination to protect his work, his hope for eventual publication for future audiences. This is an incredible opportunity to pay Benjamin the ultimate compliment, by finding and bringing together all the fragments of his work, many of which still lie undiscovered and untranslated, and bringing them together into the public domain, free from the constraints of the publishers on which Benjamin depended so desperately during his life.

The publication of his writings on technology, online, particularly his essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Mechanical Reproducibility’, but also his other writings on media, could not be more appropriate and relevant at this particular point in time. His essay on the ‘Work of Art’ has been used by many of today’s artists and theorists to understand the impact of digital technologies, as a form of reproductive technology, on art, culture and political mobilization. His arguments about the prioritization of the act of seeing, the increased speed through which information/the image in processed when reproduced by mechanical means, but also, the extent to which the technically reproduceable image is now completely removed from the actuality, and intentionality of the scene where it was initially created, remain strangely relevant today.

Interior sculpture display. at the Paris Exposition. 1900 - from Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection.

Street scene outside the Rue de Rivoli Arcades during the Paris Exposition, 1900 - from Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection.

The inability of perception to detect ‘authenticity’ – to connect the image with the original setting in which it was taken – had, according to Benjamin, important repercussions for how mass culture was re-imagined and potentially manipulated by different ideologies. Through technology, the image no longer stayed in the domain of ‘art’, but rather moved into the domain of ‘politics’. If film, the cutting edge technology at the time, served according to Benjamin: ‘to train human beings in the apperceptions and reactions needed to deal with a vast apparatus whose role in their lives is expanding almost daily’, one can easily apply a similar logic to different internet technologies today. Benjamin was however both admirative and weary of the technology of film, for the so-called ‘film capital’ could be used both in the interest of and against the masses. As we are increasingly learning today, same goes for ‘internet and social media capital.’

So many of Benjamin’s writings continue to carry important implications for the wider public today. It is perhaps high time that we remove the ‘aura’ around Benjamin’s figure – an aura built around limited accessibility to and tight control of his work – and return Benjamin and his oeuvre to his public.

Anca Pusca is Senior Lecturer in International Studies at Goldsmiths, University of London. She is the author of Walter Benjamin: The Aesthetics of Change and other articles on Benjamin which have appeared in Alternatives, International Political Sociology, Perspectives and the Journal of International Research and Development.

A selection of Benjamin’s writings are housed in German here at Wikisource, including relevant Internet Archive links.

If you are interested in helping get English translations of Benjamin’s works into the public domain then get in touch

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/10/31/on-benjamin%e2%80%99s-public-oeuvre/

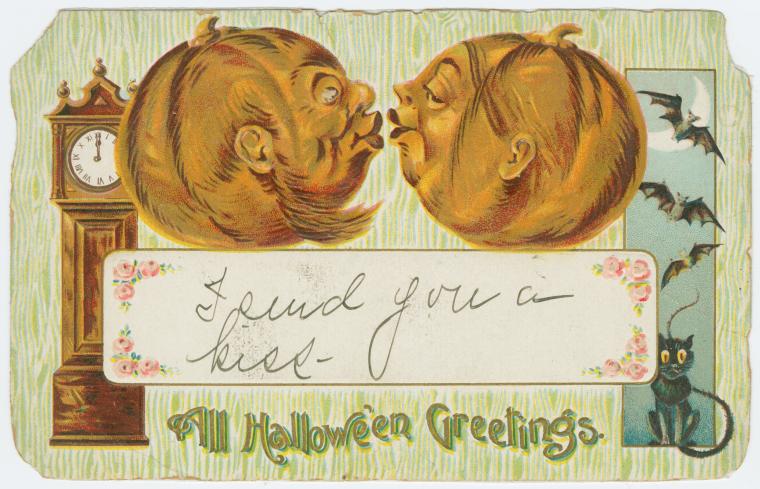

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/10/29/halloween-postcards/

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/10/28/the-diary-of-a-nobody/

At the start of his career, as a young man in his twenties, Albrecht Dürer created a series of woodcuts to illustrate Sebastian Brant’s The Ship of Fools of 1494. Dürer scholar Rangsook Yoon explores the significance of these early pieces and how in their subtlety of allegory they show promise of his masterpieces to come.

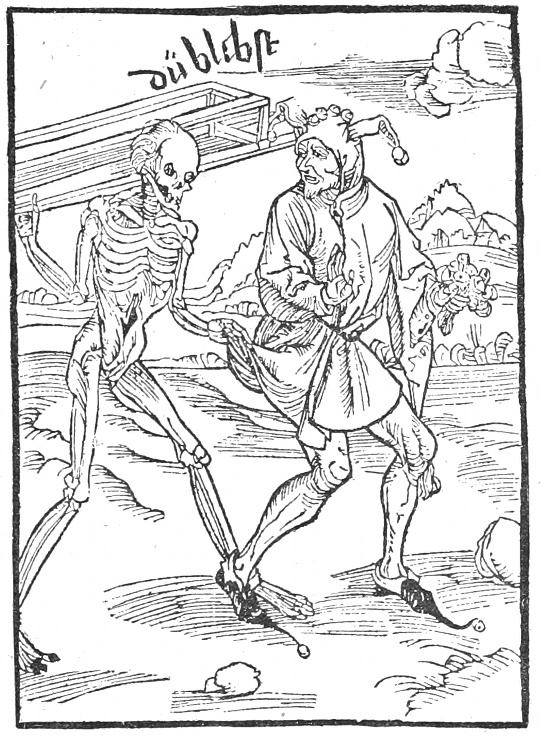

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer, woodcut illustration for Chapter 85, “Not Providing for Death”.

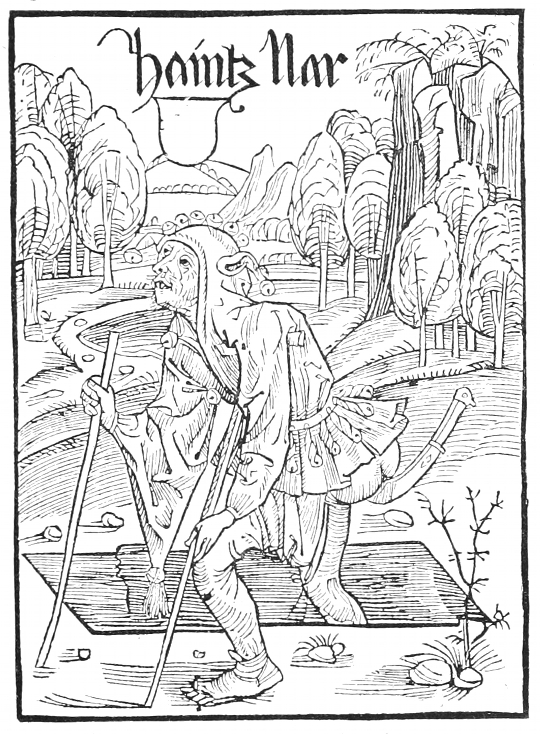

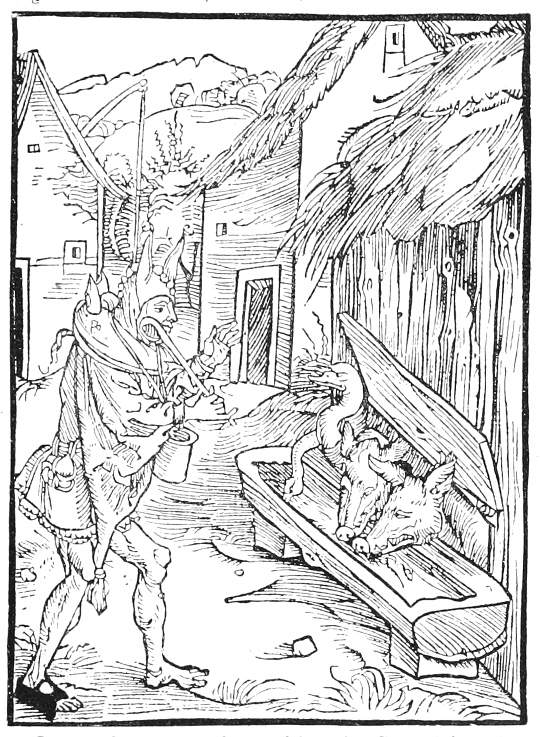

The celebrated Nuremberg artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) spent part of his journeyman years, from 1492 to 1494, in Basel, working as a woodcut designer for some of the most eminent publishers of his time, including Johann Bergmann von Olpe, Johannes Amerbach, and Nicolaus Kessler. Basel, along with Strasbourg, Augsburg and Nuremberg, was a prosperous commercial town and a leading artistic and publishing center in the North of the Alps. Dürer’s journeyman experience here was crucial in his formation as a woodcut designer deeply engaged in the early publishing industry. The most important woodcut project that he was involved with during this time was the design of an extensive illustration cycle to accompany The Ship of Fools, the satirical verses composed in German by Sebastian Brant (1457-1521) and published by Bergmann von Olpe in 1494. This collection of moralizing stories was an instant best-seller; so much so that in that same year, five separate pirated editions appeared in Strasbourg, Augsburg, Nuremberg, and Reutingen. No doubt, its numerous whimsical woodcuts depicting various types of foolish and sinful human behavior contributed to its great success, as these illustrations were copied in all subsequent editions until the late sixteenth century. Nowadays, in general, about two-thirds of the 114 illustrations (counting 9 repeating ones) in the 1494 edition are attributed to the young Dürer, while the rest, which are found inferior in design and cutting, are ascribed to anonymous masters, such as the so-called Master of the Haintz Narr (named after the namesake scene in The Ship of Fools). A more conservative view, expressed by the art historian Erwin Panofsky in 1945, attributes only one-third of the illustrations to Dürer.

The Master of the Haintz Narr, woodcut illustration for Chapter 5 , “Of Old Fools”.

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer, woodcut illustration for Chapter 14, “Of Insolence toward God”.

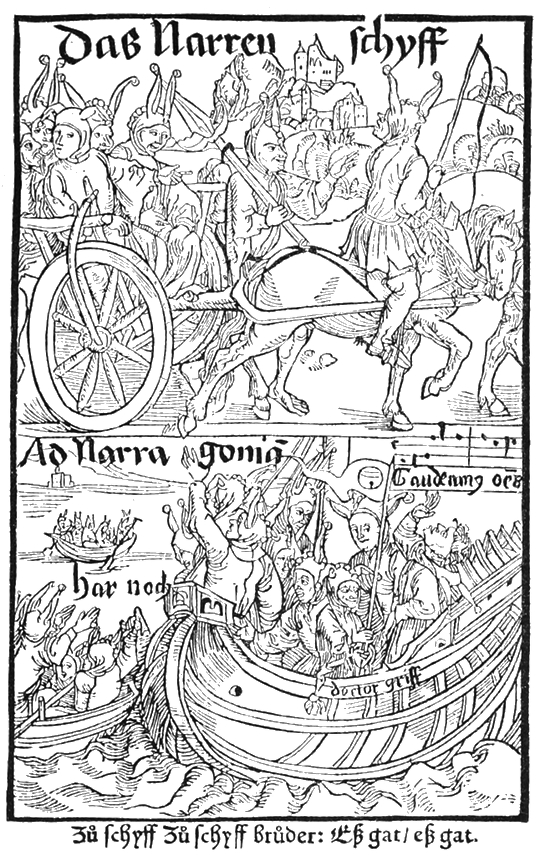

Overall, the woodcuts Dürer made during his journeyman years are not as impressive as those he created later as an independent master in Nuremberg. For example, hatching lines used for modeling consist here only of simple parallel lines, and the contour lines during this early period are depicted crudely and overly thick without much variation. The artist presumably simplified his illustrations so as to accommodate the limited skills of block-cutters (Formschneider) who were in charge of cutting the woodblocks he designed. Nevertheless, Dürer’s woodcuts in The Ship of Fools already reveal seeds of his stylistic elements and motifs found later in his career. They also betray a greater understanding of the book’s narrative and allegorical content, suggesting that he worked closely with Brant, possibly responding directly to the author’s demands and instructions. Dürer’s intimate knowledge of Brant’s text can best be illustrated by examining the original title page designed by the Nuremberg artist, The Fools on a Cart and a Boatload of Fools.

Dürer's Fools on a Cart and a Boatload of Fools, the original title page.

This woodcut of Dürer’s occupies almost the entire title page and consists of two scenes that are vertically arranged. The upper compartment shows figures in fools’ caps — shaped like donkey’s ears and adorned with bells — riding a cart pulled by horses and being guided by fools. This uppermost register also has the book’s title, “The Ship of Fools” (“Das Narren Schiff”), carved on the same woodblock as the image. In the lower section, three boats of yelling and singing rowdy fools set out for their destination, “The Land of Fools” (“Ad Narragoniam”), as indicated in the caption. Attentive viewers may find it odd that two different allegorical subjects, both the multiple ships of fools and a single cart of fools, are juxtaposed in this original title cut of 1494. It differs greatly from the better-known title cuts of later years, all of which utilize the image of only a large ship of fools, thus visualizing the book’s title verbatim. This seemingly dissonant title cut of 1494, however, confirms that Dürer was indeed well aware of the structure and themes of Brant’s original German text at the time of its conception and original publication.

Despite the book’s title, in Brant’s original text, the idea of a ‘ship’ is not central, but rather, incidental. As noteworthy as the ship is, it is only one amongst a number of diverse motifs including a cart, a dance, a wheel of fortune, a net, a mirror, and a bagpipe. The ship motif became the book’s foremost leitmotif only when, while being translated into Latin, Jacob Locher, Brant’s pupil, extensively rearranged and revised Brant’s text to give it a semblance of unity, which was found lacking in Brant’s original. This Latin edition, translated and edited by Locher and first published by Bergmann von Olpe in 1497, became the standard version of The Ship of Fools’ text that was repeatedly copied in all following editions and translations.

Given all, at the time of the book’s first publication, Dürer’s title cut, with both the cart and multiple ships, advertise the book’s full content more adequately than its short, unilateral title. It complements the title words in communicating the book’s complex, multi-structural narrative elements to the reading public, and further, it mirrors the general structure of the book.

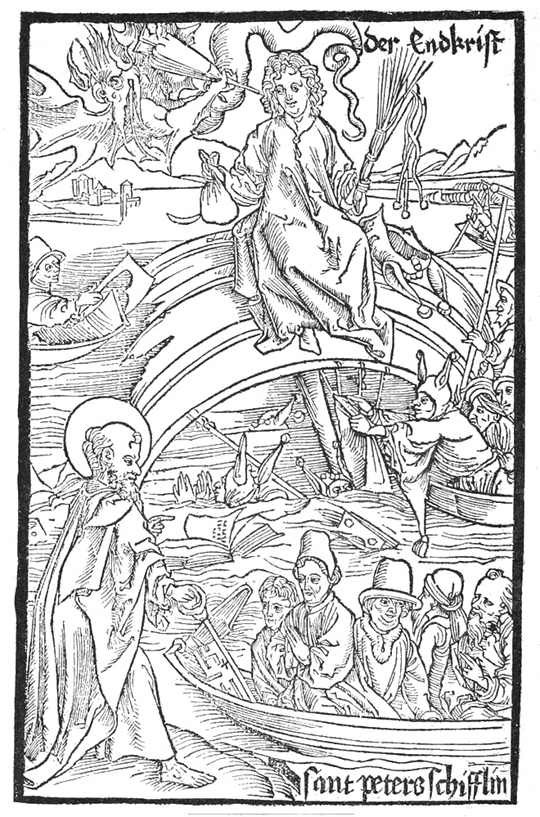

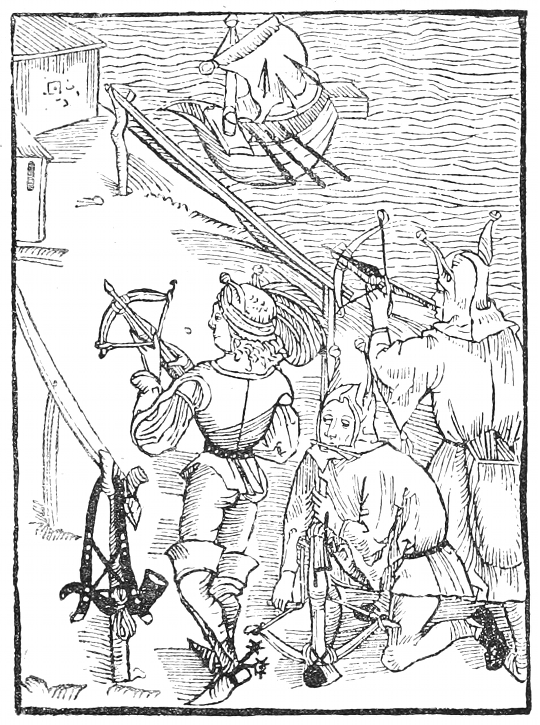

The Ship of Fools, which consists of 112 chapters, is roughly dividable into two parts. In contrast to the first half of the book (that is, the first 61 chapters), where the metaphor of a ship plays a small role except in chapter 48 (“A Journeyman’s Ship”), the ship motif is disproportionately greater in the second half: the prologue (since it was written last) and chapters 103 (“Of the Antichrist”), 91 (“Of Prattling in Church”), 108 (“The Schluraffen Ship”), and 109 (“ Contempt of Misfortune”). We gather that Brant gradually realized its symbolic importance in the process of his writing. The significance of the ship in the second part is even more apparent when one examines the text illustrations. Even when the ship is only briefly mentioned, or even not mentioned at all, it is still visually depicted, sometimes as a tiny object floating on a lake (or a sea) in the background, and sometimes far more conspicuously. This can bee seen in chapters 68 (“Not Taking a Joke”), 72 (“Of Coarse Fools”), 75 (“Of Bad Marksmen”), 80 (“Foolish News”), and 81 (“Of Cooks and Waiters”).

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer, woodcut illustration for chapter 103 , “Of the Antichrist”.

Attributed to Albrecht Dürer, woodcut illustration for chapter 75, “Of Bad Marksmen”.

The motif of a cart of fools is treated as a principal theme only twice in the book, once in chapter 47 (“On the Road of Salvation”) and another time in chapter 91 (“Of Prattling in Church”), where both the cart and the ship are addressed simultaneously. Less emphatically, the cart motif is mentioned once again in chapter 53 (“Of Envy and Hatred”). However, Dürer’s depiction of the cart, along with ships, on the title page serve well as metaphors for land- and sea-going vehicles carrying the fools, thus conveying the universality of all the fools described by the text.

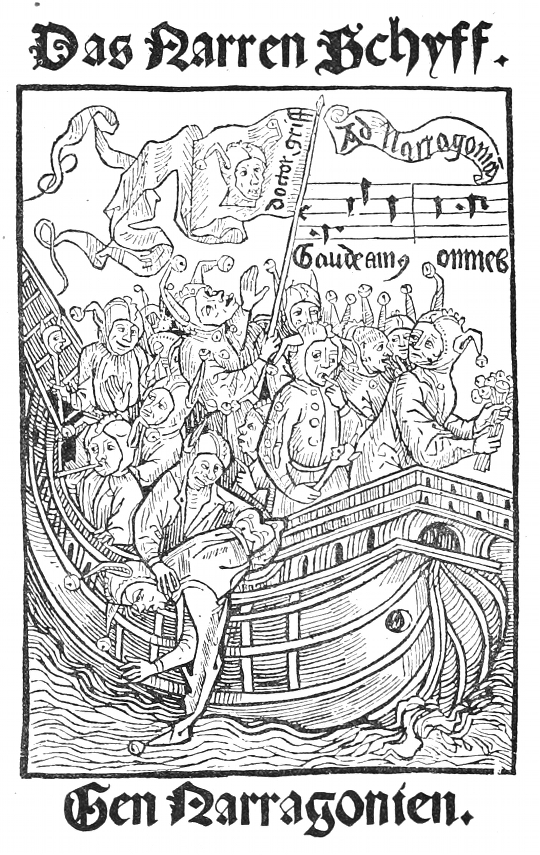

With the editorial changes made to Brant’s text by Locher, who utilized ‘the ship of fools’ as the leitmotif throughout, not only in the first Latin edition of 1497 but also in all subsequent publications (both authorized and pirated), the book no longer reproduced or imitated the original title page design by Dürer. Instead, after 1497, a different woodcut, rendering only a large ship laden with fools and attributed to the Master of the Haintz Narr, repeatedly served as the title cut prototype. In 1494, the Master of the Haintz Narr’s woodcut originally appeared as the frontispiece on the verso of the title page, and also can be found as an illustration accompanying chapter 108, “The Schluraffen Ship.” As the concept of the ship became the most significant motif of the book, this woodcut became the most fitting image for the title cut, as it visualizes the two principal ideas of the book and its title — namely, both a ship and fools. However, it is Dürer’s original title cut for the 1494 edition which represents the book’s original structure and thematic concerns much more faithfully and allegorically.

Master of Haintz Narr, the frontispiece of the 1494 edition which became a popular choice for title page in later editions.

Throughout his career as a successful independent master in Nuremberg, Dürer continued to create woodcuts that were meant to accompany texts. He provided numerous humanist friends and Nuremberg publishers with woodcuts to illustrate their new publications. Best known works, of course, are his own illustrated books, such as the Apocalypse (1498; the second edition in 1511), the Large Passion (1511), the Life of the Virgin Mary (1511), and the Small Passion (1511). Here, the primary features are the woodcuts themselves, rather than texts, and significantly, he self-published them by hiring printers. Dürer’s later productions of such high caliber, innovation, and audacity cannot be fully understood without taking into consideration his invaluable journeyman experience in the large publishing companies and his participation in executing extensive illustration cycles such as The Ship of Fools in Basel.

Rangsook Yoon is Assistant Professor of Art History at Central College in Pella, Iowa, specialising in Dürer’s early career as a print-maker and self-publisher. She is currently working on several articles dealing with Dürer’s woodcuts during his apprenticeship and journeyman years, as well as a book about the Apocalypse.

For Alexander Barclay’s 1874 English translation (but with illustrations from the 1497 Latin version) see here and here.

Source: http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/10/25/navigating-durer%e2%80%99s-woodcuts-for-the-ship-of-fools/