A century on from his dramatic death on the way back from the South Pole, the memory of the explorer Captain Scott and his ill-fated Terra Nova expedition is stronger than ever. Max Jones explores the role that the iconic visual record has played in keeping the legend alive.

The photographer Herbert Ponting giving a lecture on his travels in Japan to the Terra Nova team in the hut at Cape Evans.

Why are some historical figures remembered, while others are forgotten?

Major-General Henry Havelock was the toast of the nation in 1857. One of the British heroes of the ‘Indian Mutiny’, Havelock died after the relief of the city of Lucknow. Such was the fame of the devout Christian soldier, parliament approved the erection of his statue in Trafalgar Square, which still stands today. A decade ago, however, Mayor Ken Livingstone complained that most Londoners had no idea who Havelock was.

The memory of Captain Scott, who died in Antarctica one hundred years ago, has fared much better than Havelock’s. The centenary of Scott’s last expedition has generated a wave of books, events, radio broadcasts and television documentaries over the last two years, including BBC 2’s The Secrets of Scott’s Hut fronted by modern celebrity-explorer Ben Fogle, a major new exhibition at the Natural History Museum, and a national memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Scott’s exploits in the uninhabited continent of Antarctica are free of the troubling associations which surround many other imperial heroes. Should the statue of a man known primarily for subjugating India still stand in the centre of a city where over one in ten of the inhabitants have roots in South Asia? As with so many aspects of our imperial past, Britons have found it easier to ignore and forget rather than confront such difficult questions.

In part, of course, Scott is remembered today because his last expedition is such a great story: the drama of the race with Norwegian Roald Amundsen; the heart-breaking arrival at the South Pole a month too late; the agonising suspense of the return march; the tragic end only 11 miles from a supply depot which would have saved them. Yet a great story alone offers no guarantee of remembrance. Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition and his incredible boat journey to South Georgia were surprisingly neglected in Britain until the end of the 1990s.

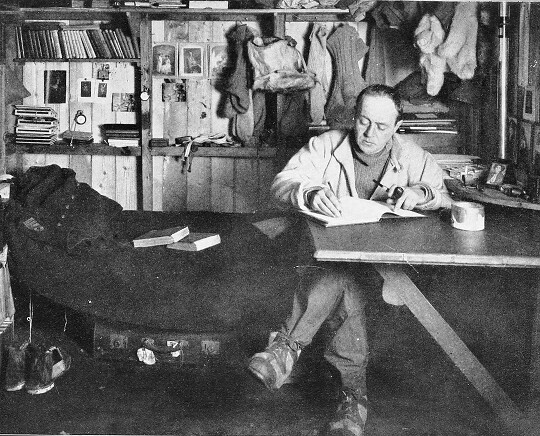

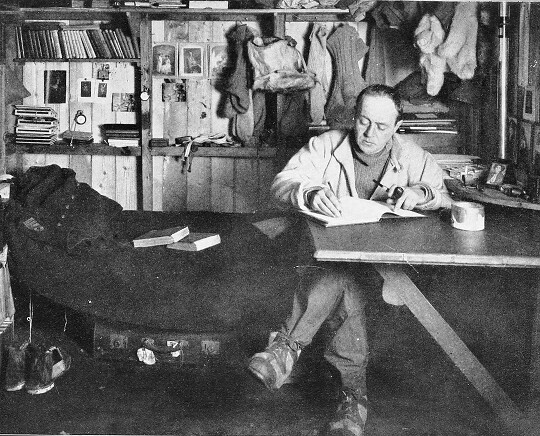

Captain Scott writing in his journal.

Interior of the hut at Cape Evans with Cherry Garrard, Bowers, Oates, Meares and Atkinson.

Elsewhere1, I have emphasised the significance of Scott’s own words to his continued remembrance. The ‘Message to the Public’ Scott wrote at the back of his journal remains one of the ultimate expressions of bravery in the face of death. Scott’s journals are on permanent display as one of the ‘Treasures of the British Library’. The centenary celebrations would have been far less extensive if a search party had not found the journals in November 1912.

But visual iconography has also proved essential to sustaining Scott’s story. His decision-making has been widely criticised, most savagely in Roland Huntford’s classic debunking biography Scott and Amundsen (London, 1979). Scott deserves great credit, though, for his appointment of Herbert Ponting as the expedition’s self-styled ‘camera artist’. Ponting’s early life remains obscure, but we know he abandoned his family to pursue a full-time career in photography. He later observed that he wouldn’t even recognise his own son if he walked past him on the street.

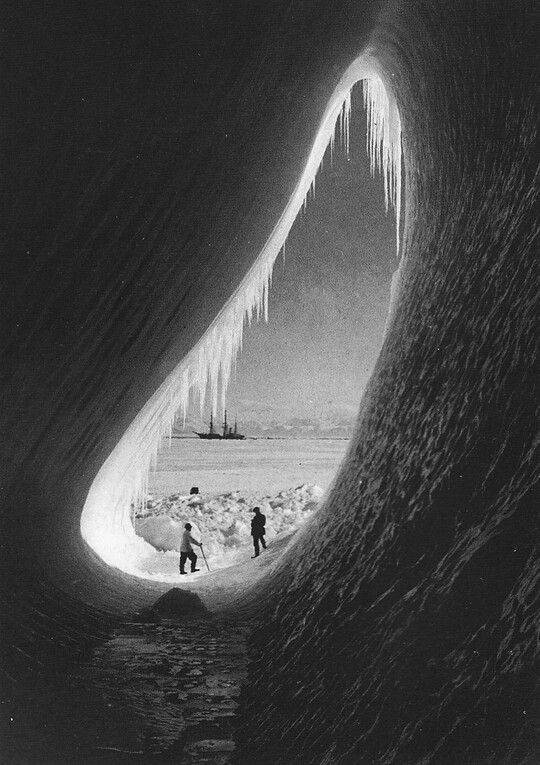

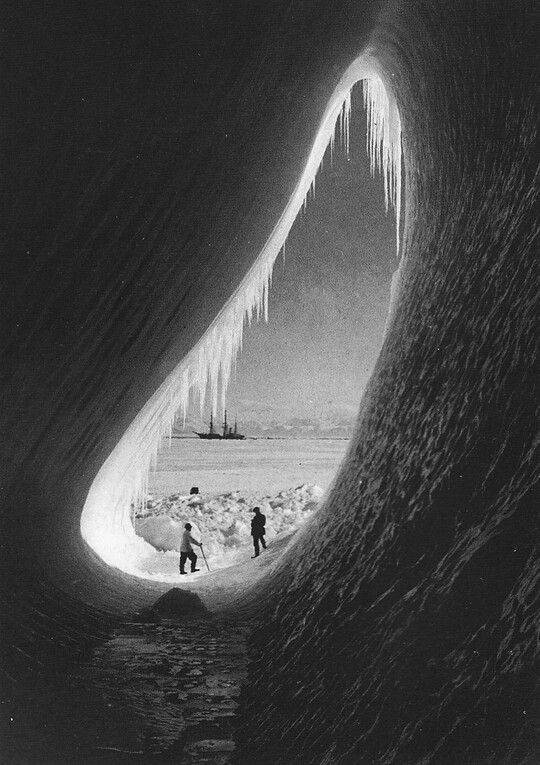

Ponting exposed around 25,000 feet of film and 2,000 photographic negatives in the Antarctic. Rarely, if ever, has an expedition been documented so thoroughly and so beautifully. Publishers and film-makers today can be confident of the availability of rich visual resources for any new Scott project, with striking photographs of the central characters, wild life and Antarctic environment. Ponting frequently juxtaposed awe-inspiring natural features with tiny human figures, presenting the Antarctic as a medieval fortress besieged by brave polar knights.

The castle berg in summer

Photograph taken in January 1911 of Taylor and Wright at the entrance of an ice grotto near Cape Evans. The ship Terra Nova is anchored in the background.

In 1914, Ponting mounted a hugely successful series of illustrated lectures about the expedition at the Philharmonic Hall, performing in front of 100,000 people in only two months. The lectures proved so successful, King George V invited him to give a special performance at Buckingham Palace. Ponting had the misfortune, however, of purchasing the complete rights to the expedition’s film record from the Gaumont Company just before the outbreak of the First World War. Ponting would spend much of the next two decades attempting to exploit his Antarctic work, but never matched the success of the Philharmonic Hall lectures.

Although his work continues to shape visual representations of Antarctica, Ponting did not take the most famous photograph of Scott’s last expedition. The explorers themselves exposed ten plates at the South Pole. In one they appear to slouch around Amundsen’s tent like rock stars on an album cover. Henry Bowers pulled the cord which took the most iconic image of the Antarctic disaster. This photograph remains the most frequently reproduced: five grim faces marked by hardships endured and the certain knowledge of hardships to come, the forlorn union jack a reminder of their defeat. The survival of this remarkable photograph helps explain the enduring appeal of Scott’s story. In 2000 Hello Magazine published two special editions celebrating ‘The 20th Century in Pictures’, ‘An Heirloom to Treasure’. Scott, Bowers, Evans, Oates and Wilson stared out from the front cover.

Photograph taken by Lieut. Bowers on 17 January 1912, a day after they reached the SOuth Pole to discover that Amundsen had beat them to it. The two sitting are Evans and Oates, with Bowers, Scott and Wilson standing behind them.

Scott and his men at Amundsen's base, Polheim. Left to right: Scott, Bowers, Wilson, and P. O. Evans.

The grave of Scott, Bowers and Wilson, erected at their final camp where their bodies were found.

Dr Max Jones is a Senior Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Manchester. He is the author of The Last Great Quest: Captain Scott’s Antarctic Sacrifice (Oxford UP, 2003) and the editor of Journals: Captain Scott’s Last Expedition (Oxford World’s Classics)

(Oxford UP, 2003) and the editor of Journals: Captain Scott’s Last Expedition (Oxford World’s Classics) (Oxford UP, 2005). Max has been invited to lecture on Scott to audiences in Los Angeles, Milan and Tasmania. He is currently working on a new book on the rise and fall of national heroes over the last 250 years.

(Oxford UP, 2005). Max has been invited to lecture on Scott to audiences in Los Angeles, Milan and Tasmania. He is currently working on a new book on the rise and fall of national heroes over the last 250 years.

Links to Works

- The Great White South; being an account of experiences with Captain Scott’s South pole expedition and of the nature life of the Antarctic (1922), by Herbert Ponting.

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!