On 21st November 1811, on a lake’s edge near Potsdam, a 34 year old Kleist shot himself dead in a suicide pact with his terminally ill lover. He left behind him just under a decade of intense literary output which has established him as one of the most important writers of the German romantic period. On the bicentenary of his death, Kleist scholar Steven Howe explores the importance of his first dramatic work and how in it can be seen the themes of his later masterpieces.

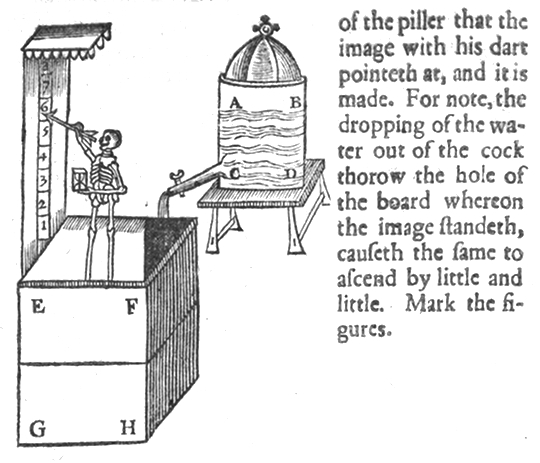

Chalk-drawing reproduction of a now lost miniature which Peter Friedel made in 1801 to be presented to Kleist's fiancée at the time Wilhelmine von Zenge

Heinrich von Kleist is without doubt one of the most challenging figures in German literary history. In a career lasting a little under a decade, from 1802 through to his premature death in 1811, he produced a remarkable body of creative work that radically called into question the prevailing intellectual, aesthetic and ethical orthodoxies of the age. Today, Kleist is perhaps most familiar, certainly to British audiences, as the dramatist behind the violently tragic Penthesilea and the brilliantly enigmatic The Prince of Homburg, and as the author of a series of daring and dramatic short stories, including Michael Kohlhaas, The Marquise of O…, and The Earthquake in Chile. Altogether less well-known, however (notwithstanding Eric Bentley’s adaptation in German Requiem), is his first major literary production, the five act play The Schroffenstein Family, published in 1803. Aside from a brief premiere at the National Theatre in Graz in January 1804, the drama found little immediate resonance, and it has traditionally been regarded as belonging to the second class of the author’s imaginative work. Kleist, for his part, also seems to have attached little value to the piece, referring to it in a letter to his sister, Ulrike, as a ‘wretched botched job’. That the drama suffers from the defects one might expect of the first work of a young poet is a point that few would demur: the language is overwrought, the plot convoluted, and the entire exposition lacks the refined touch which Kleist was later to perfect. That being said, the play nonetheless contains a number of scenes and episodes which provide an early glimpse of the author’s promise and genius, and introduces several of the most significant themes and features which were to subsequently become a hallmark of his poetics.

The action of the drama revolves around the conflict between the rival houses of Rossitz and Warwand, and the fate of two star-crossed lovers, Ottokar and Agnes. The imaginative debt to Romeo and Juliet is plain to see, and Kleist hews closely to the model of Shakespeare’s tragedy, though with one significant variation – the two feuding houses are here different branches of the same family. The origins of the conflict extend from a testamentary contract, according to which the property of either house should fall to the other branch if the line of descent is broken. This breeds an atmosphere of mistrust, as both houses suspect one another of pursuing its demise, and particularly that of its heirs. When the younger son of Count Rupert, head of the Rossitz branch of the family, dies in unexplained circumstances, his suspicions thus fall directly on his counterpart, Count Sylvester, and the drama opens with him compelling his immediate family to swear an oath of bloody and absolute vengeance against the entire house of Warwand.

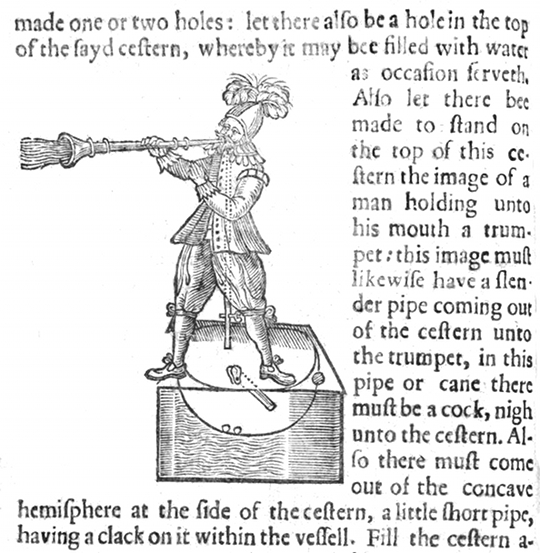

The cast of characters of Die Familie Schroffenstein as featured in a 1922 collection of Kleist's works for the stage.

The tragic trajectory of the play is set by the issue that Ottokar, the elder son of Rupert, partakes in this oath-swearing, unaware that the girl with whom he has fallen in love, Agnes, is the daughter of Sylvester. Once alerted to the fact, he is convinced by Agnes of her father’s innocence in the matter of the child’s death and attempts to negotiate a reconciliation between the warring counts. His efforts are thwarted, however, by Rupert’s burning hatred for Sylvester and his untameable lust for revenge. Upon learning of his son’s clandestine affair, Rupert resolves to murder Agnes, and when the two lovers secretly meet at a mountain cave, he and his vassal, Santing, accost them. In an attempt to deceive his father and protect his beloved, Ottokar exchanges clothes with Agnes; failing to note the switch in the darkness, Rupert stabs his own son to death, whereupon the presently arriving Sylvester follows suit by murdering Agnes in the mistaken belief that she is Ottokar. Ironically – or perhaps appropriately – it falls to the blind grandfather, Sylvius, to recognise the true identities of the two victims and reveal the double filicide. At the play’s end, an old widow, Ursula, discloses the true state of affairs, namely that Rupert’s son’s death was accidental – he drowned in a forest brook. With the misunderstanding resolved, a despairing reconciliation follows, and the drama closes with the mad-driven bastard son of the Rossitz house, Johann, addressing Ursula as master and personification of fate.

That the mechanisms of fate and chance do serve as an important motor for the action of the drama is very much an accepted commonplace in interpretive criticism. In his personal letters, Kleist reveals a fascination with the unknowable powers of contingency and coincidence that intrude upon and shape the life of the individual, and such concerns penetrate to the core of many of his literary works: time and again, he confronts his characters with situations over which they have no control and to which they must then react. In Schroffenstein, chance happenings are heaped upon one another in such a way as to both blunt much of the originality of the constellation, and to strain reader credulity after the fashion of the Gothic tale – it is not without reason that Matthew G. Lewis’s The Monk has been cited as a possible source of inspiration. The outcome is a demonstration of the operations of fate and contingency which, viewed in a narrow sense, seems at times laboured and contrived. The design of the inquiry is, however – in a further parallel to Romeo and Juliet – overlaid with a deeper disquisition on the limitations of human awareness. Ursula’s laconic words to Rupert and Sylvester, ‘If you kill one another, it is an error’, acquire, in this context, special relevance, pointing as they do towards the movement of error and the instances of misunderstanding that drive the action to its tragic close. Here one can detect the influence of Kleist’s encounter with Kantian philosophy, which appears to have shattered his faith in the possibilities of absolute truth and knowledge. The fallibility of perception emerges, as a consequence, as a dominant theme and subject of reflection in Kleist’s work, and remains so across his entire literary corpus. In Schroffenstein, this manifests itself through the frequent recurrence of error and confusion, bred by the characters’ inability to communicate and their attendant susceptibility to misreading reality. Typically, Kleist drives the issue towards aesthetic extremes, crafting an enveloping atmosphere of illusion, deceit and suspicion within the extended family which, in turn, calls forth gruesome acts of vengeance and retributive violence. In this regard, the drama can perhaps be seen as the most Jacobean and Sturm und Drang-like of Kleist’s works – as a grizzly, though at times darkly comedic, exploration of the workings of fate and the human capacity for misunderstanding, and of their effects in unleashing man’s violent potentialities.

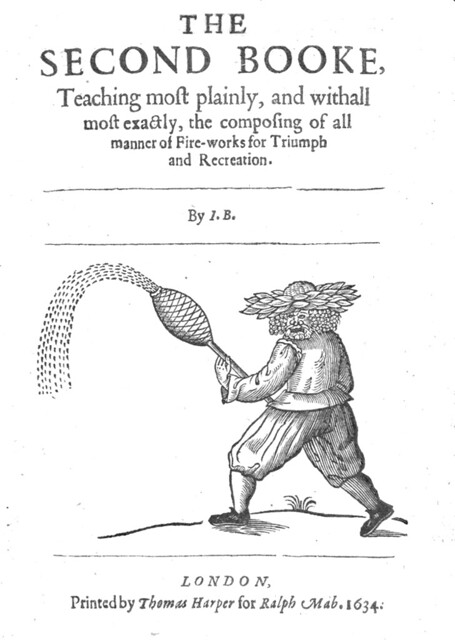

Kleist's grave alongside that of Henrietta Vogel, his terminally ill lover whom he shot before shooting himself in a suicide pact on the banks of Kleiner Wannsee near Potsdam. The inscription on Kleist's grave reads 'Now, oh immortality, you are all mine'.

(Photo by Jochen Jansen, published under a CC-BY-SA license).

It would be misleading, however, to suggest that the tragedy be approached solely through the lens of metaphysical and epistemological concerns. For the very issue of error that stands at the heart of the drama raises the question of interpretation, and with it that of the extent to which cultural and social codes give shape to the individual’s understandings and perceptions. In particular, the text displays how the nature of the conflict between the two houses fosters a socially-conditioned prejudice that colours and impairs judgement, and which speaks to a deeper cultural critique embedded within the drama. The major point of reference and orientation here is Jean-Jacques Rousseau who, in his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, both put into question the Enlightenment faith in human progress and delivered a searing assault on the conditions of modernity. The opening scene of the play already bears the mark of Rousseau’s sway: when Rupert’s wife, Eustache, refers to her natural feminine tenderness in response to his calls for her to swear the oath of vengeance, he objects, ‘Nothing more of nature. It is but a sweet, delightful fairytale from childhood’. What follows does so under the sign of Rousseau’s condemnation of man’s fall from natural goodness into socio-moral decay: the terms of the inheritance contract, for instance, as both agent and symbol of the conflict between Rupert and Sylvester, casts into relief the lure of wealth and property, the original idée fixe, which Rousseau identifies as a root cause of modern inequality and conditions of violence. In its presentation of the trials of the lovers, meanwhile, the text also plays on the anthropology of identity laid down in the Discourse, in which the dilemma of man’s ruinous modernity is diagnosed in terms of the tensions between subject and world. In this instance, that dilemma is telescoped through the relationship between love and society, with Ottokar in particular forced to struggle with the contrast between the demands of his father and his feelings for Agnes. In such a way, the text also points to a modern view of identity as an active positioning of the self in relation to cultural discourses – a theme to which Kleist was to frequently return, perhaps most notably in his portrayal of the cross-cultural relationships between Gustav and Toni in The Betrothal in St. Domingo, and between Achilles and Penthesilea in the drama of the latter name.

These fundamental tensions between nature and culture, between individual and society, serve as a central axis for the greater part of Kleist’s literary oeuvre, and it is perhaps in this sense, above all, that Schroffenstein can be seen to point the way towards his later – and greater – dramatic achievements. On the one hand, his works dwell on the onslaught of fate that upsets the secure ideals of enlightenment rationalism; on the other, however, this aspect is only ever a corollary to a deeper sense of the cultural rift between subject and world, and the attendant instabilities of agency and identity. Behind this lies the experience of the French Revolution and the turmoil it left in its wake, as existing hierarchies of power and status collapsed, and Europe was plunged into a period of instability and conflict. Against this backdrop, Kleist, like so many of his Romantic contemporaries, critically explores the paradigms of eighteenth-century humanist discourse, taking up the tensions and paradoxes embedded therein and exhibiting them in the full light of his imagination. In particular, it is the complex relationship between nature and culture to which he time and again returns, with most of his texts turning upon an exploration of the psychological and moral conflicts between the individual and his or her environment. Frequently, such struggles escalate to a sudden unleashing of the self, to acts of violent rebellion or assimilation. It is this readiness to plumb the extreme depths of human psychology and conduct under conditions of stress that lends Kleist’s work its peculiar modernism, and which ensures that even now, some two hundred years on from his death, he retains the ability to excite, engage and trouble his readers.

Steven Howe is Associate Research Fellow in the College of Humanities at the University of Exeter. He is currently working, together with Ricarda Schmidt (Exeter) and Sean Allan (Warwick), on a large-scale, AHRC-funded project – timed to coincide with the bicentenary of the author’s death – exploring discourses of education and violence in the works of Heinrich von Kleist (Kleist, Education and Violence: The Transformation of Ethics and Aesthetics). He has previously written a full-length study on Kleist’s engagement with the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and published further articles regarding the representation of violence in Kleist’s texts, and on aspects of their popular and critical reception.

Links to Works

- Text version of Die Familie Schroffenstein (in German)

Sämtliche Werke und Briefe – Vol. 1 (1908) by Heinrich von Kleist featuring Die Familie Schroffenstein.

Tales from the German, comprising specimens from the most celebrated authors (1844) containing Kleist’s classic Michael Kolhaus translated into English by John Oxenford and C.A. Feiling.