When a volcano erupted on a small island in Indonesia in 1883, the evening skies of the world glowed for months with strange colours. Richard Hamblyn explores a little-known series of letters that the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins sent in to the journal Nature describing the phenomenon – letters that would constitute the majority of the small handful of writings published while he was alive.

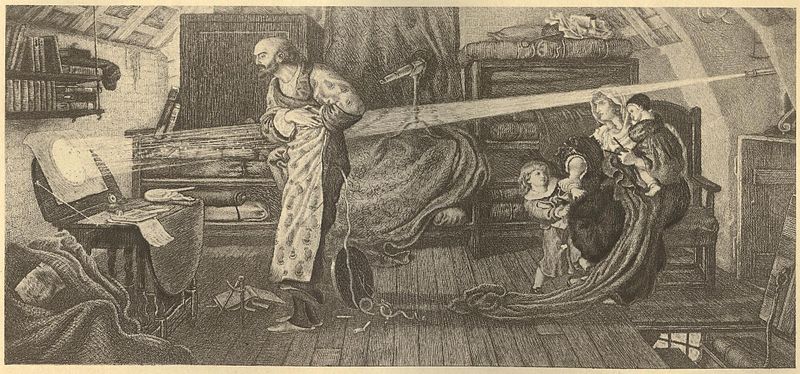

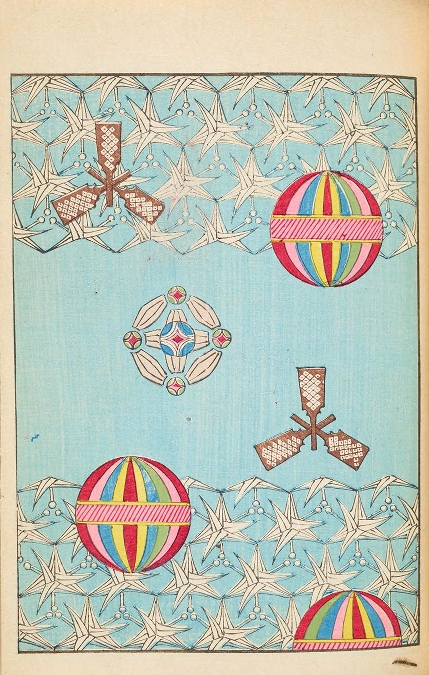

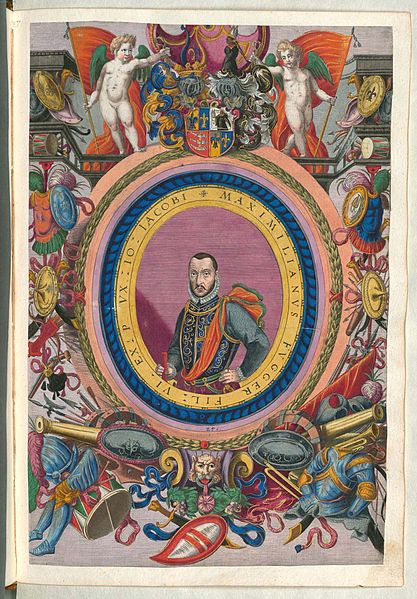

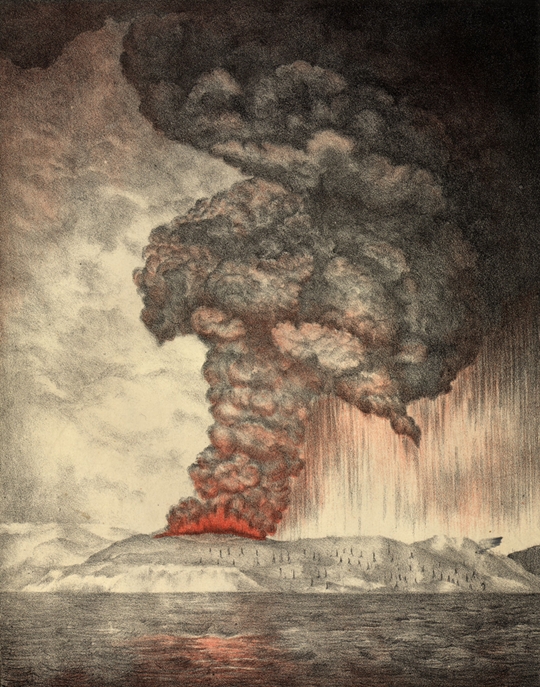

Lithograph from 1888 showing the Krakatoa eruption, author unknown.

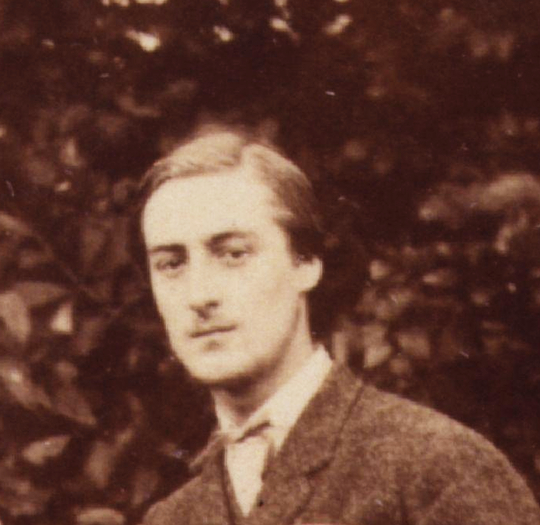

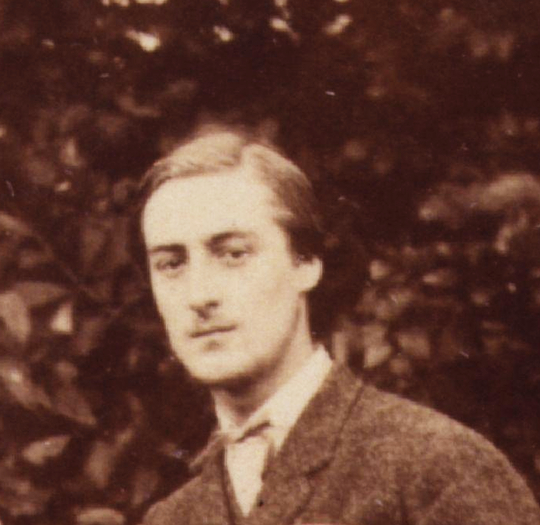

During the winter of 1883 the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins descended into one of his periodic depressions, “a wretched state of weakness and weariness, I can’t tell why,” he wrote, “always drowsy and incapable of reading or thinking to any effect.” It was partly boredom: Hopkins was ungainfully employed at a Catholic boarding school in Lancashire, where much of his time was spent steering his pupils through their university entrance exams. The thought that he was wasting his time and talents weighed heavily upon him during the long, brooding walks he took through the “sweet landscape” of Ribblesdale, “thy lovely dale”, as he described it in one of the handful of poems he managed to compose that winter. He was about to turn forty and felt trapped.

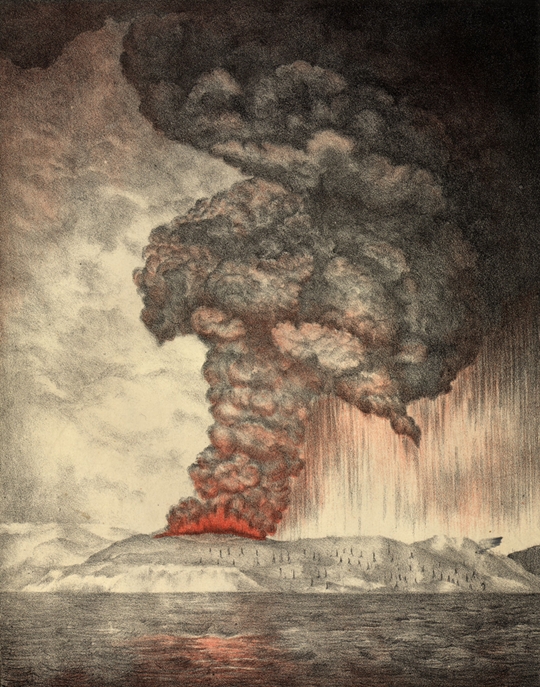

Such was his state of mind when the Krakatoa sunsets began. The tiny volcanic island of Krakatoa (located halfway between Java and Sumatra) had staged a spectacular eruption at the end of August 1883, jettisoning billions of tonnes of ash and debris deep into the earth’s upper atmosphere. Nearly 40,000 people had been killed by a series of mountainous waves thrown out by the force of the explosion: the Javan port of Anjer had been almost completely destroyed, along with more than a hundred coastal towns and villages. “All gone. Plenty lives lost”, as a telegram sent from Serang reported, and for weeks afterwards the bodies of the drowned continued to wash up along the shoreline. Meanwhile, the vast volcanic ash-cloud had spread into a semi-opaque band that threaded slowly westward around the equator, forming memorable sunsets and afterglows across the earth’s lower latitudes. A few weeks later, the stratospheric veil moved outwards from the tropics to the poles, and by late October 1883 most of the world, including Britain, was being subjected to lurid evening displays, caused by the scattering of incoming light by the meandering volcanic haze. Throughout November and December, the skies flared through virulent shades of green, blue, copper and magenta, “more like inflamed flesh than the lucid reds of ordinary sunsets,” wrote Hopkins; “the glow is intense; that is what strikes everyone; it has prolonged the daylight, and optically changed the season; it bathes the whole sky, it is mistaken for the reflection of a great fire.”

Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1866, detail from a photo by Thomas C. Bayfield. National Portrait Gallery

In common with most other observers at the time, Hopkins had no idea what was causing the phenomenon, but he grew fascinated by the daily atmospheric displays, tracking their changing appearances over the course of that unsettled winter. At the end of December he collated his observations into a remarkable 2,000-word document, which he sent to the leading science journal, Nature. The article, published in January 1884, was a masterpiece of reportage, a heightened prose poem that mixed rhapsodic literary experimentation with a high degree of meteorological rigour:

Above the green in turn appeared a red glow, broader and burlier in make; it was softly brindled, and in the ribs or bars the colour was rosier, in the channels where the blue of the sky shone through it was a mallow colour. Above this was a vague lilac. The red was first noticed 45º above the horizon, and spokes or beams could be seen in it, compared by one beholder to a man’s open hand. By 4.45 the red had driven out the green, and, fusing with the remains of the orange, reached the horizon. By that time the east, which had a rose tinge, became of a duller red, compared to sand; according to my observation, the ground of the sky in the east was green or else tawny, and the crimson only in the clouds. A great sheet of heavy dark cloud, with a reefed or puckered make, drew off the west in the course of the pageant: the edge of this and the smaller pellets of cloud that filed across the bright field of the sundown caught a livid green. At 5 the red in the west was fainter, at 5.20 it became notably rosier and livelier; but it was never of a pure rose. A faint dusky blush was left as late as 5.30, or later. While these changes were going on in the sky, the landscape of Ribblesdale glowed with a frowning brown. (from G. M. Hopkins, “The Remarkable Sunsets”, Nature 29 (3 January 1884), pp. 222-23)

Hopkins was a gifted empirical observer with a near-forensic interest in the search for written equivalents to the complexity of the natural world. Such interest in the language of precision was shared by many scientists at the time, science, like poetry, being an inherently descriptive enterprise. Anyone who reads the official Royal Society report on the Krakatoa sunsets (published in 1888) will find flights of poetic prose to rival those of Hopkins, who described such language as “the current language heightened and unlike itself,” a dynamic written form that was particularly suited to the expression of what he called “inscape”: the distinctive unity of all natural phenomena that gives everything in nature its characterising beauty and uniqueness. The force of being that holds these dynamic identities together he termed “instress”, instress being the essential energy that enables an observer to recognise the inscape of another being. These post-Romantic notions formed a kind of personal poetic creed, a logocentric natural theology that was rooted in the work of Duns Scotus, the medieval Christian philosopher.

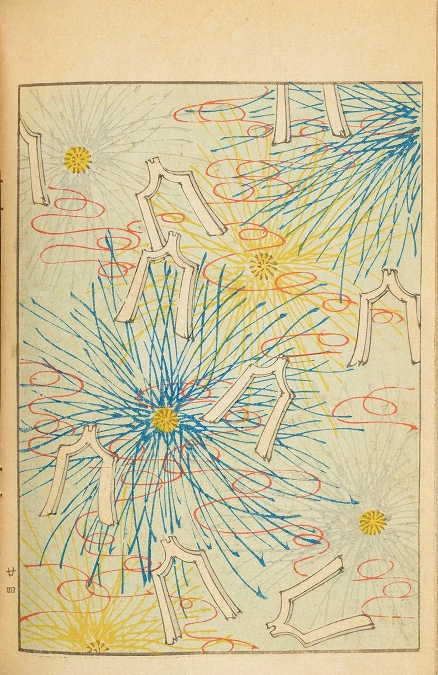

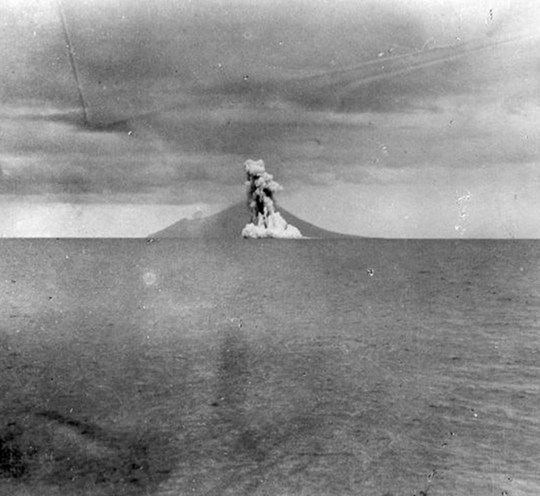

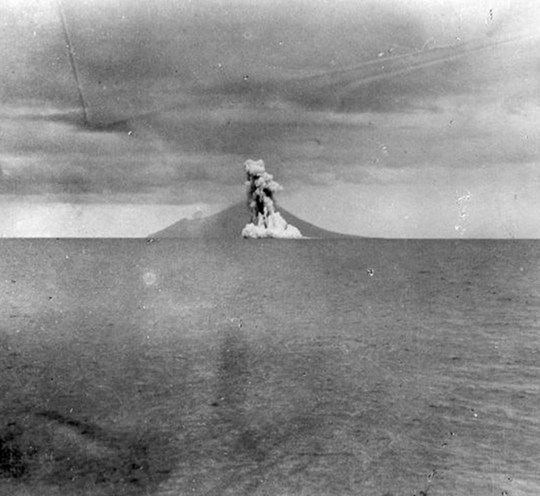

Photograph taken in 1928 of the destroyed Krakatoa island resurfacing, forming what is known now as 'Anak Krakatau', or 'Child of Krakatoa'. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT).

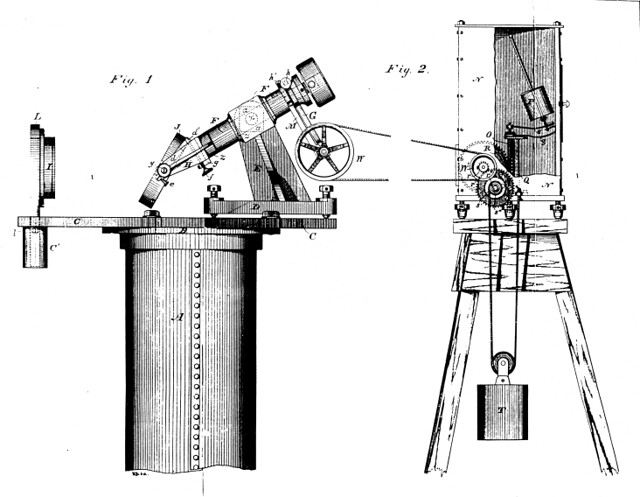

For Hopkins, inscape and instress lay at the heart of his religious and poetic practice, as well as being vital means of apprehending the natural world. In a journal entry for 22 April 1871, for instance, he records “such a lovely damasking in the sky as today I never felt before. The blue was charged with simple instress, the higher, zenith sky earnest and frowning, lower more light and sweet.” Note that he felt the damasking as well as saw it, and note, too, his calibrated descriptions of the banded blues of the sky, the higher “earnest and frowning”, the lower “more light and sweet.” His journals are full of such poetic quantifications, which he used as notes towards a quintet of articles that he published in the journal Nature, all on meteorological subjects. The first two, published in November 1882 and November 1883, were letters describing anti-crepuscular rays (cloud-shadows that appear in the evening sky opposite the sun), while the following three were all on the subject of the Krakatoa sunsets, which had evidently furnished the melancholy Hopkins with a much-needed source of distraction.

He was not alone in his interest; all over the world, writers, artists and scientists responded to the drama of the volcanic skies. The poets Algernon Swinburne, Robert Bridges and Alfred Tennyson (then poet laureate), wrote lengthy descriptive strophes prompted by the unearthly twilights, although, as the historian Richard Altick pointed out, “the only good poetry that resulted from the celestial displays is found in Hopkins’ prose” (Richard D. Altick, “Four Victorian Poets and an Exploding Island”, Victorian Studies 3 (March 1960), p. 258). This is a fair assessment, though I do have a sneaking fondness for Tennyson’s blank-verse approximation of the cadences of Victorian popular science:

Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak

Been hurl’d so high they ranged about the globe?

For day by day, thro’ many a blood-red eve . . .

The wrathful sunset glared . . . (“St. Telemachus”, pub. 1892)

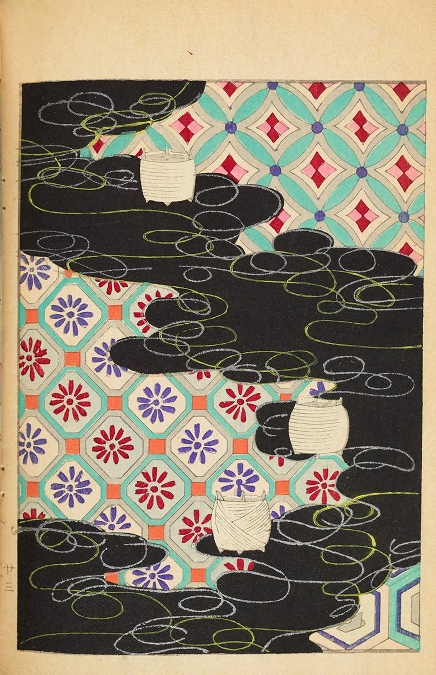

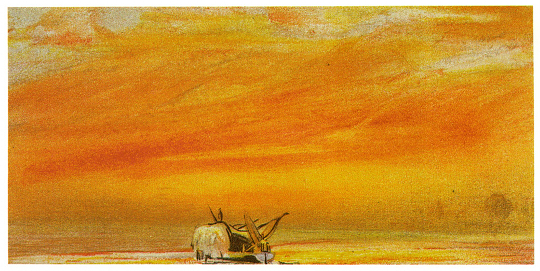

Visual artists also found themselves extending their colour ranges in awed emulation of the skies. Painter William Ascroft spent many evenings making pastel sky-sketches from the banks of the Thames at Chelsea, noting his frustration that he “could only secure in a kind of chromatic shorthand the heart of the effect, as so much of the beauty of afterglow consisted in concentration.” He exhibited more than five hundred of these highly-coloured pastels in the galleries of the Science Museum, in the repository of which they remain to this day, little known and rarely seen.

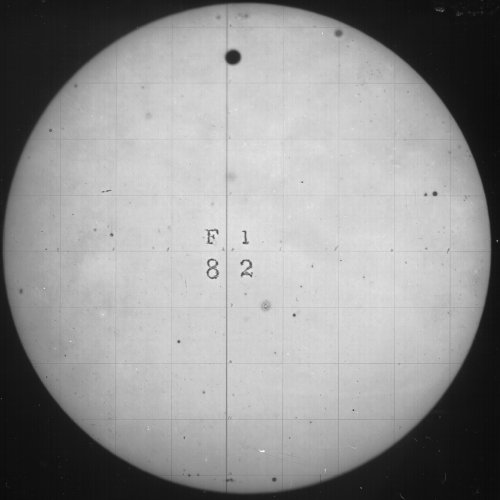

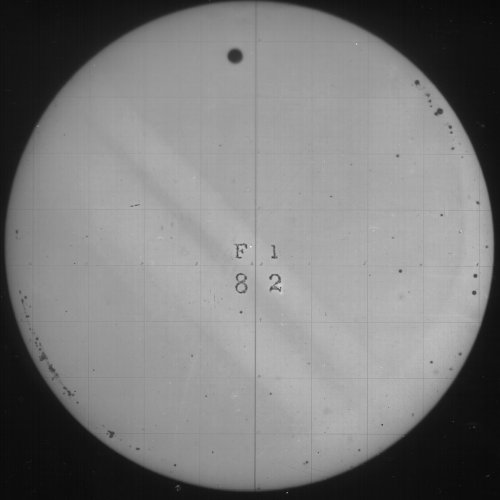

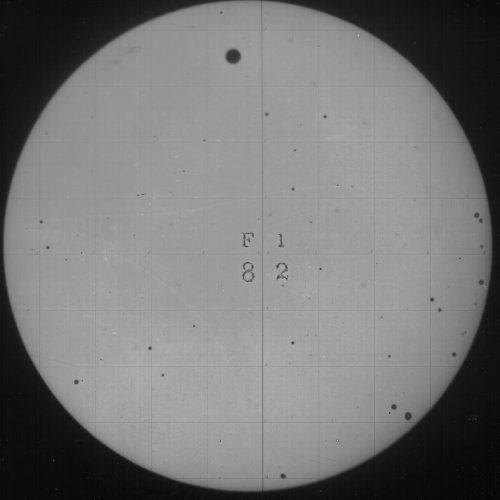

Three of the hundreds of sketches carried out by William Ascroft in the winter of 1883/4 - used as the frontispiece of The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of the Krakatoa committee of the Royal Society (1888), ed. by G.J. Simmons.

In Oslo, by contrast, the sunsets helped inspire one of the world’s best-known paintings: Edvard Munch was walking with some friends one evening as the sun descended through the haze: “it was as if a flaming sword of blood slashed open the vault of heaven,” he recalled; “the atmosphere turned to blood – with glaring tongues of fire – the hills became deep blue – the fjord shaded into cold blue – among the yellow and red colours – that garish blood-red – on the road – and the railing – my companions’ faces became yellow-white – I felt something like a great scream – and truly I heard a great scream.” His painting The Scream (1893), of which he made several versions, is an enduring (and much stolen) expressionist masterpiece, a vision of human desolation writhing beneath an apocalyptic sky, as “a great unending scream pierces through nature.” As it happens, the final eruption of Krakatoa on 27 August 1883 was the loudest sound ever recorded, travelling almost 5,000 km, and heard over nearly a tenth of the earth’s surface: a great scream indeed.

As for Hopkins, the publication of his Krakatoa essay coincided with the welcome offer of a professorship in classics at University College Dublin. He left Lancashire for Ireland in February 1884, relieved to have made his escape. It didn’t last. Homesick, lonely and overworked, Hopkins succumbed to his worst depression yet, his misery traced in the so-called “terrible” sonnets of 1885 (“I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day”). He died of typhoid fever in June 1889 (aged 44), and was buried in an unmarked grave. Only his close friend Robert Bridges was aware of his greatness as a poet, and the bulk of his work remained unpublished until 1918. In fact, apart from a handful of minor poems that had appeared in obscure periodicals, the five Nature articles were the only works that Hopkins published in his lifetime.

Richard Hamblyn’s books include The Invention of Clouds , which won the 2002 Los Angeles Times Book Prize and was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize; Terra: Tales of the Earth

, which won the 2002 Los Angeles Times Book Prize and was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize; Terra: Tales of the Earth (2009), a study of natural disasters; and The Art of Science

(2009), a study of natural disasters; and The Art of Science (2011), an anthology of readable science writing from the Babylonians to the Higgs Boson. He is a lecturer in creative writing at Birkbeck, University of London.

(2011), an anthology of readable science writing from the Babylonians to the Higgs Boson. He is a lecturer in creative writing at Birkbeck, University of London.

Links to Works

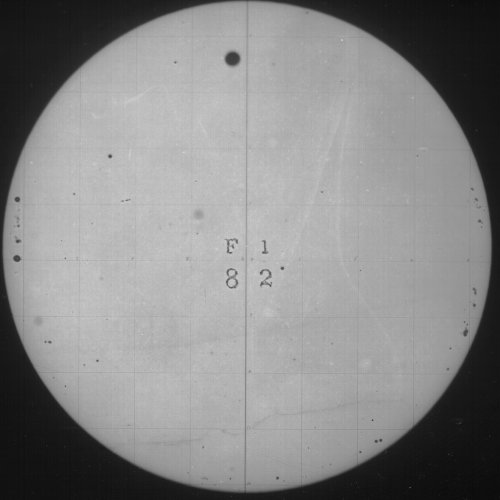

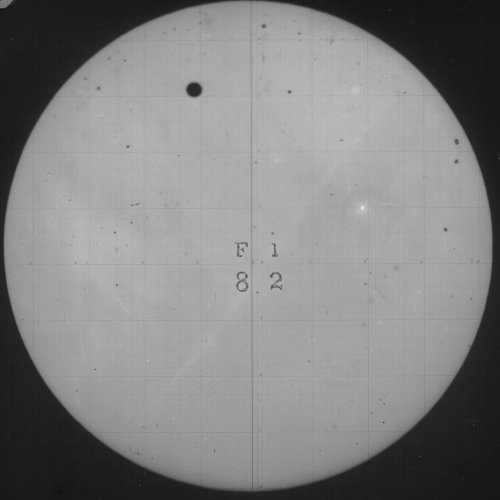

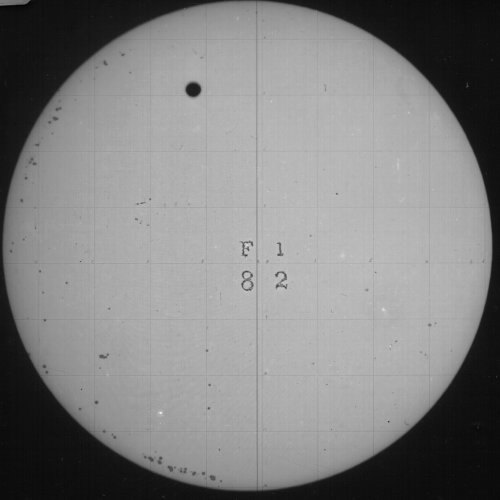

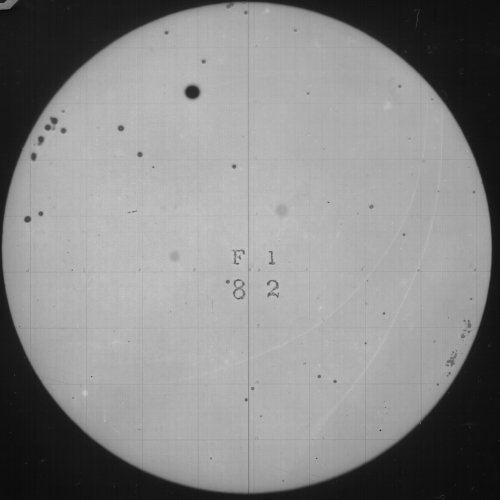

Letters by Gerard Manley Hopkins in Nature, Vol XXIX, November 1883 to April 1884.

Letter by Gerard Manley Hopkins in Nature, Vol XXVII, November 1882 to April 1883.

The Eruption of Krakatoa, and Subsequent Phenomena: Report of the Krakatoa committee of the Royal Society (1888), Ed. by G.J. Simmons.

Sign up to get our free fortnightly newsletter which shall deliver

direct to your inbox the latest brand new article and a digest of the

most recent collection items. Simply add your details to the form

below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your

subscription!

Sign up to get our free fortnightly newsletter which shall deliver

direct to your inbox the latest brand new article and a digest of the

most recent collection items. Simply add your details to the form

below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your

subscription!