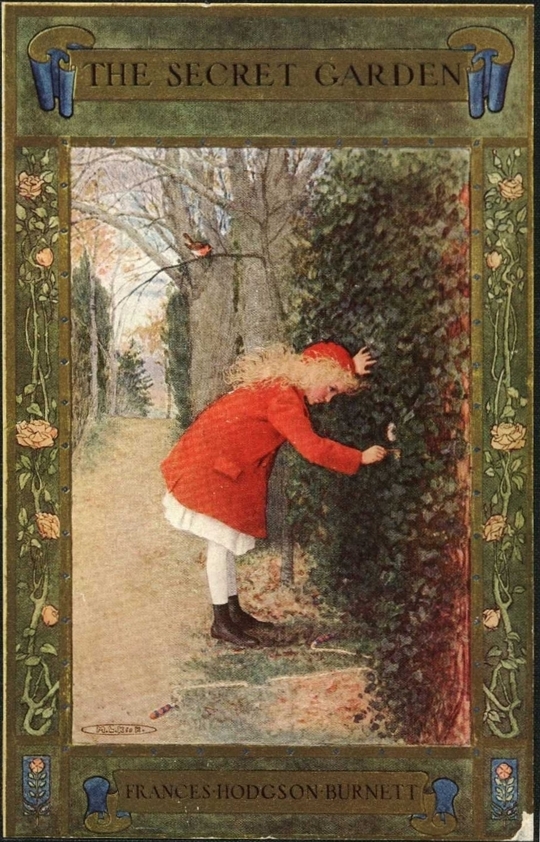

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the children’s classic The Secret Garden. Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, author of Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Unexpected Life of the Author of The Secret Garden, takes a look at the life of Burnett and how personal tragedy underpinned the creation of her most famous work.

“With regard to The Secret Garden,” Frances Hodgson Burnett wrote to her English publisher in October 1910, “do you realize that it is not a novel, but a childs [sic] story though it is gravely beginning life as an important illustrated serial in a magazine for adults. . . . It is an innocent thriller of a story to which grown ups listen spell bound to my keen delight.” The “thriller of a story” made its first appearance that fall in The American Magazine, but appeared as an actual book a year later.

Now, as the novel is celebrated during its centennial year, it’s fascinating to go back and see the modest beginning of a book that is repeatedly cited as one of the most influential and beloved children’s books of all time. Yet Burnett would be astonished today to learn that she is known primarily as a writer for children, when the majority of her fifty-three novels and thirteen produced plays were for adults.

When Burnett sat down to write the story of an orphaned girl sent from India to the Yorkshire moors, where she helps herself and others find redemption and health by reviving a forgotten garden, she composed it not in the north of England but in her new home on Long Island. Born in 1849 and raised in Manchester, England into a middle class family, she moved as a teenager to Tennessee when her widowed mother decided they should emigrate at the end of the Civil War. Although they were poor, Burnett was delighted at giving up the grit and smoke of a factory city for the stunning landscapes of eastern Tennessee. In America she soon began to publish her romantic stories in some of the most popular magazines, eventually becoming hugely famous when she published her sixth novel, Little Lord Fauntleroy, in 1886. From the first her work had never been turned down by any publisher, but with Fauntleroy she became, and remained, the highest paid woman writer of her time, churning out books and stories with great regularity. Despite the enormous success of Fauntleroy, and later of A Little Princess, most of her novels and plays were not for a juvenile audience.

By this time a married mother of two living in Washington, DC, she capitalized on her English background in most of her work. Over the years, England remained an active and important part of her life. She crossed the Atlantic no fewer than thirty-three times over her lifetime, often living abroad for a year or two at a time. At the same time, she maintained homes in Washington, and later in New York, and doted upon her very American sons, even when her marriage to their father broke down and through some surprisingly long absences from them.

Two life-changing events contributed to the genesis of The Secret Garden, which was written late in her life. The first was the death of her sixteen-year-old son Lionel, who became increasingly ill in Washington while she was living away. Her husband, Dr. Swan Burnett, wrote her urgent letters about their son’s failing health, but it was not until the diagnosis turned out to be tuberculosis that she rushed home to take Lionel on a desperate circuit of European spas. When he died in her arms in Paris at the end of 1890, she was completely devastated. For years she threw herself into starting and supporting a clubhouse for boys in London, and in spoiling her remaining son, Vivian.

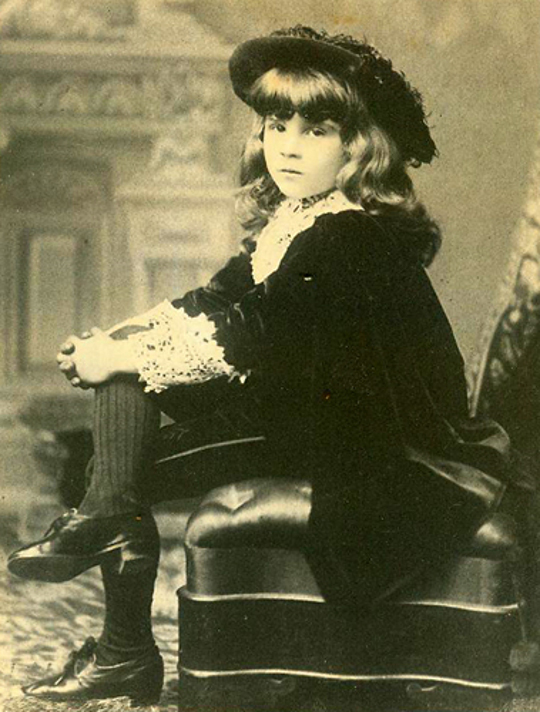

Vivian Burnett dressed as 'Little Lord Fauntleroy'

The second loss was that of her beloved home Maytham Hall in Kent, in southern England, which she had leased for ten years. In 1908 the leaseholder decided to sell the grand house, and Burnett was forced to leave the home where she had spent the happiest months of each year, after shedding her abusive second husband. There she cultivated extensive gardens, held parties, and tamed a robin as she wrote outdoors at a table in a sheltered garden. Both the robin and the gardens made their way into The Secret Garden.

With the loss of Maytham Hall, Burnett returned to America where she built adjoining houses for herself and her sister Edith, and for Vivian and his family in Plandome, on Long Island. She returned for several long sojourns to England, and spent her winters with Edith in Bermuda. In both Bermuda and Plandome she threw herself into gardening, with the help of gardeners, designing extensive gardens that produced award-winning blooms. Roses were her favorite, and her trademark, just as they were for Lilias Craven in The Secret Garden.

Every year Burnett published a book in time for the Christmas market, and in 1910 she found herself intrigued by the thought of a sallow and unlikeable little girl, her disabled cousin, and a strong nature-loving boy and his benevolent mother. Always taken with her own writing – she often declared that they “came” to her rather than being invented, and she could sometimes be found reading her own books on a stairway, with evident pleasure — she wrote to her publisher that “I love it myself. There is a long deserted garden in it whose locked door is hidden by ivy and whose key has been buried for ten years. It contains also a sort of Faun who charms wild creatures and tame ones and there is a moorland cottage woman who is a sort of Madonna with twelve children — a warm bosomed, sane, wise, simple Mother thing.”

Burnett loved the combination of the gothic and the natural worlds, and the ability of children to understand and appreciate them in everyday life. In this new story, she was able, whether she recognized it or not, to recover from her two enormous losses. Unlike her son Lionel, Colin Craven is restored to health at the end of the novel. And unlike Maytham Hall, the gardens at Misselthwaite Manor continually bloomed. When Burnett died in 1924, her friends helped erect a memorial to her in Central Park, consisting of a fountain surrounded by gardens and reading benches. Their prescient choice of The Secret Garden for the fountain sculpture surprised the public, for it was, at the time, one of her lesser known and appreciated books, but they knew these were things that were close to the author’s heart.

Although it sold well enough at first, The Secret Garden lapsed into a kind of near oblivion for many decades. Critics ignored or disparaged it, even at a time when children’s literature began receiving more and more critical and scholarly attention. It was the children, along with librarians, who saved it, passing on the book to readers and friends, and creating a special place in their hearts for the story. By the 1960s, its fortunes began to revive, and when the book went out of copyright in 1986, dozens of illustrators and publishers rushed to reproduce it.

As we celebrate 100 years of The Secret Garden, the book has never been more popular or influential. Whole shelves in bookstores carry its many editions, and it has been translated into nearly every known language. Children around the world continue to love the story of the children who, with the help of nature and positive thinking, bring the world back to life. As Burnett said to a friend, “I know quite well that it is one of my best finds.” Children and adults one hundred years later, still agree.

Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina is chair of the department of English at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, and teaches courses on the novel, biography, Bloomsbury and black literature of Britain and America. She is the author or editor of seven books, including a biography of Frances Hodgson Burnett and two editions of “The Secret Garden”. Her most recent book is “Mr. and Mrs. Prince: How an Extraordinary Family Moved out of Slavery and Into Legend”. She hosts the nationally-syndicated radio program “The Book Show”, interviewing authors on their recent books of literary fiction, biography and history.

Links to work

- The Secret Garden (1911)