This week sees the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Titanic, one of the deadliest peacetime disasters at sea. Richard Howells, author of The Myth of the Titanic, explores the various legends surrounding the world’s most famous ship.

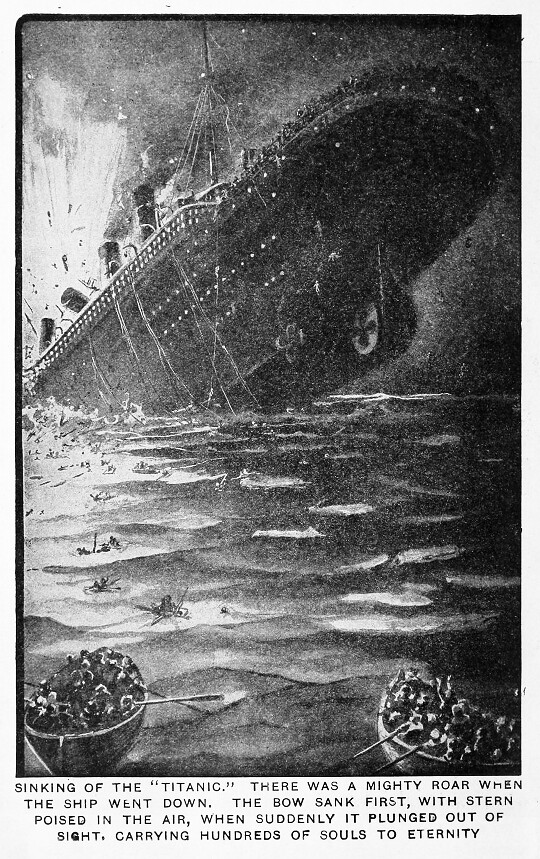

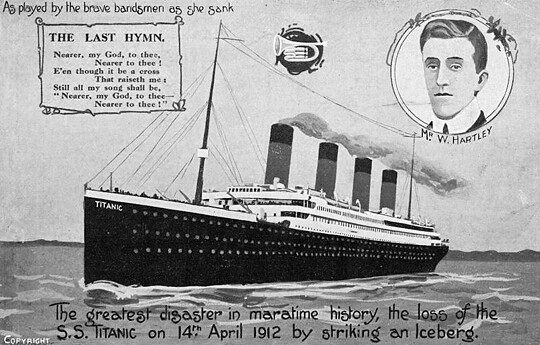

Nearer, My God, To Thee was said to be played by the ship's band as it sank. Illustration for the Toledo News-Bee via Marshall Everett, Story of the Wreck of the Titanic

There can be no one, surely, reading this article who has not already heard of the Titanic. And there can be no one among them, equally certainly, who does not already know how the story of the Titanic ends. This is, when we think about it, really quite remarkable. There is no one alive today who actually remembers the Titanic: all the survivors are dead. For the rest of us, there is very little possibility that the disaster has directly affected us, personally or historically.

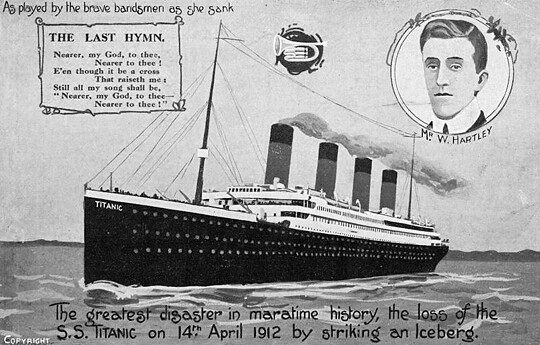

And yet… as we mark the 100th anniversary of the sinking on April 15th 1912, the world is full of it. We hear the repeated exhortation: “remember the Titanic” even though not one of us literally can. And yet… ask people and they will tell you not just about the iceberg, but probably also about the lifeboats, “women and children first”, and the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as the ship finally sank with the loss of some 1,500 lives. The captain, of course, went down with his ship.

But most of all they will tell you about the “unsinkable ship”, the biggest and finest ever built, the last word in luxury that sank, seemingly inevitably, on its first and only voyage. They said that “God himself could not sink this ship”, but on “her” maiden voyage “she” was duly ripped asunder.

There are two remarkable things about this. First that a 100 year old story continues to be told and re-told. Second that many of the component stories are simply not true. And fore-most amongst these is the big one: that prior to its departure from Southampton, the Titanic was feted by all as the “unsinkable ship”. It wasn’t. So how do we explain all this? The answer is that 100 years on, the sinking of the Titanic has long-since passed from history and into myth.

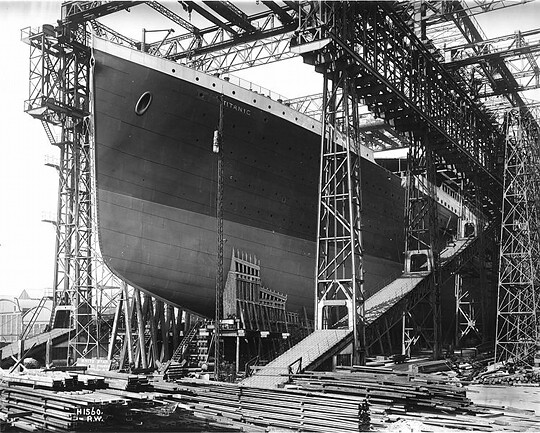

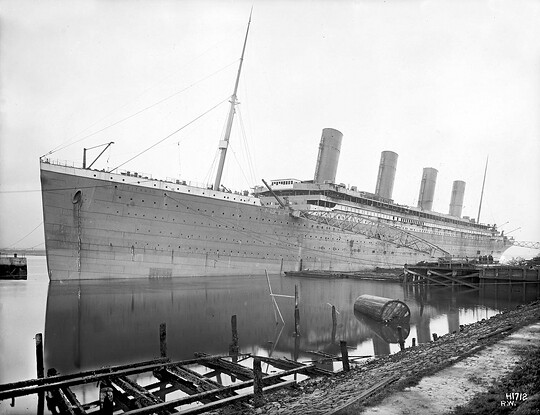

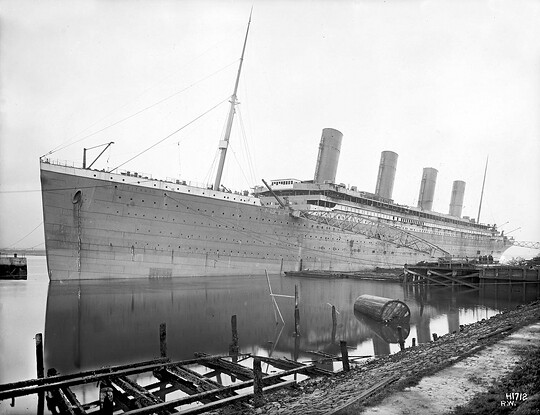

RMS Titanic and its identical sister ship RMS Olympic under construction at Harland Wolff shipyards, Belfast, ca. 1910

In the common parlance, a myth is a falsehood –or at very least an enduring popular misconception. But intellectually, a myth is much more complex and revelatory than that. A myth is more accurately a story (or an amalgam of stories) that may (or may not) be historically true but which contains a series of cultural truths embedded in narrative form. In this way it may (like a fable or a parable) not be “true” in the literal sense, but we can still say “there is a lot of truth in that story.” More than that, the content of the story tends both to flatter the teller and –crucially- to serve to make sense of a seemingly random universe. This is precisely the case with the Titanic.

When we study myths from an anthropological perspective and proceed to turn that scholarly gaze upon ourselves, we can see our changing and different selves reflected therein. Myths are not limited to distant, past, exotic or “primitive” peoples, and the Titanic is just such an evolving, modern myth that we continue to tell about ourselves. It is also a migratory narrative that is re-articulated in an expanding variety of media forms from print to postcards, books, music, television, merchandising and computer games. No medium, however, exemplifies this better than the feature film.

Films of the Titanic typically make great claims for their accuracy but in reality part very quickly from the historical record. The infamous “Nazi” Titanic film of 1943, for example, had the audacity to invent and place a German officer on board, who proceeded to give dire warnings to the British crew about the reckless inefficiency of it all. Inevitably, it was he who spotted the iceberg first and lived to give damning evidence at the official inquiry –but not before he had gallantly rescued a small child from her watery bed. Hollywood’s first “Titanic” feature (1953) showcased an entirely fictitious American family in pursuit of solid, mid-Western values, while Britain’s “A Night to Remember” (1958) is about class as much as it is about seamanship. Lew Grade’s “Raise the Titanic” (1980) is a totally fanciful Cold War parable; James Cameron’s multi-award winning “Titanic” of 1997, on the other hand, made great claims for its historical authenticity but centred upon a totally invented core of characters –none of whom (it must be repeated) ever existed. We are left, however, with the warm glow of personal fulfilment, cross-class possibilities, the pleasure of being poor and –most of all- true love beyond price. And if, finally, we cross into television, Julian Fellowes’ 100th anniversary “Titanic” mini-series is a well-shaken cocktail of actual and imaginary characters who interact as if nothing impossible were in fact taking place. The resulting concoction, of course, bears the distinct flavour of Britain not in 1912 but in 2012.

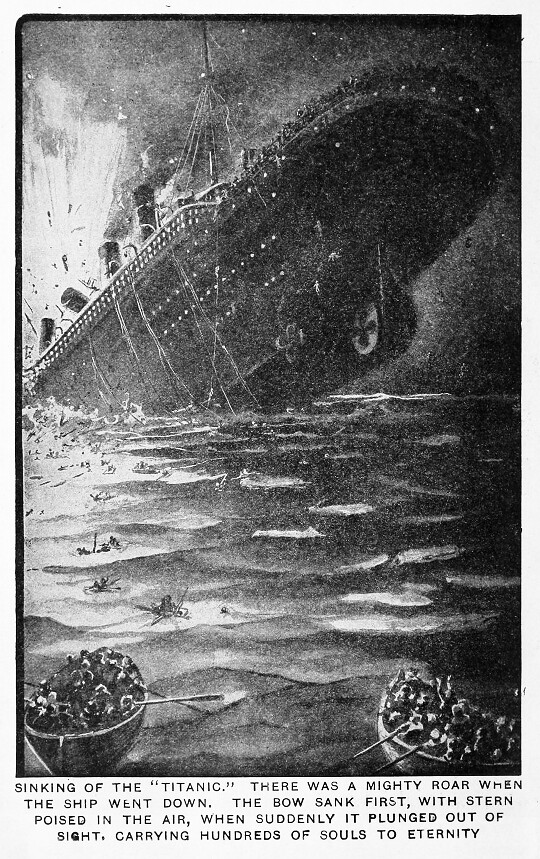

Illustration from Sinking of the Titanic, most appalling ocean horror (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray

Postcard featuring an inset of Mr W Hartley, the ship's bandmaster whose band apparently played Nearer, My God, To Thee as the ship sank

When we study popular cultural representations of the Titanic in whatever medium in close-up, we see the values of the culture, era, and society that made them in vivid reflection. A study of the Titanic in British popular culture from 1912 to the start of the First World War, for example, reveals distinctly late-Edwardian understandings of race, religion, class and gender, crowned by the captain’s much celebrated (but historically unverified) last order to his crew: “Be British!”

These historical snapshots are of immense value to the cultural sociologist, while to the semiotician they demonstrate once again the inherently flexible relationship between the signifier and the signified: The Titanic sinks consistently in the popular imagination, but the values that go down with it remain many and varied according to the particular perspectives of the tellers of the tale in both time and space.

Individual examples are individually revealing, but structural anthropologists such as Claude Lévi-Strauss remind us that in order to get a make a thorough analysis of a myth we need to understand it as a composite of all its component versions. So, in addition to the particular and ‘local’ variations we need to stand back and take stock of the overwhelming, universal themes. Consistent among all versions of the myth of the Titanic is the notion of the vessel as the “unsinkable” ship which sank on “her” maiden voyage. No version of the myth is complete without this fundamental ingredient, and it is an ingredient which will be more than familiar to students of classical mythology as a reworking of the Hellenic themes of Hubris and Nemesis.

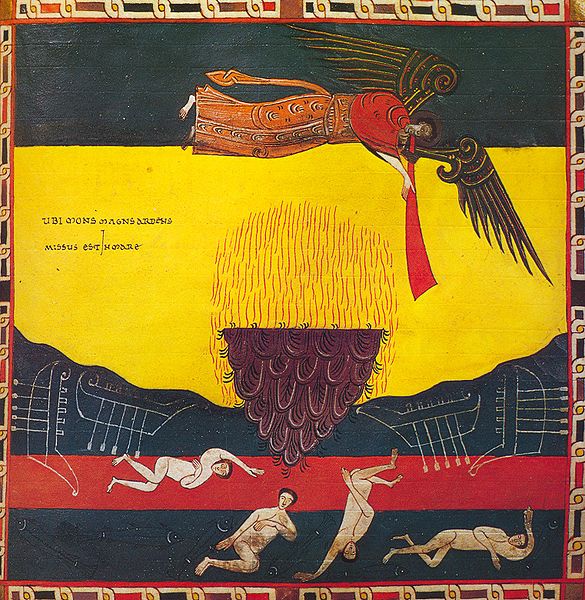

In Greek mythology, Hubris is pride –usually that of man over-reaching himself in the face of the Gods. This is especially the case when man seeks to overcome nature which is the Gods’ rightful domain. So, we see the mortal Prometheus stealing the secret of fire from Zeus, and Icarus escaping the bonds of earth by flying with wings of wax. Inevitably and swiftly, Hubris results, for the Gods are vengeful. Prometheus has his liver pecked out by an eagle on a daily basis, while Icarus flies too near the sun: his wings melt and he falls to his death in the sea.

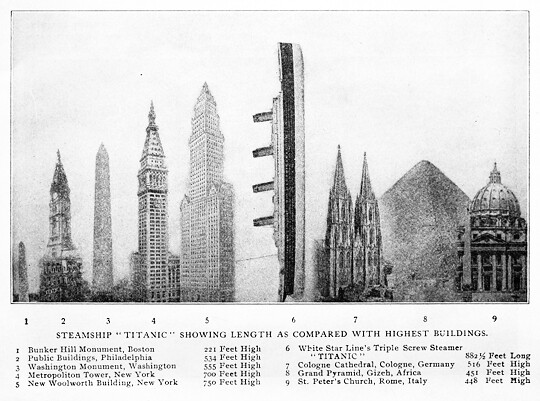

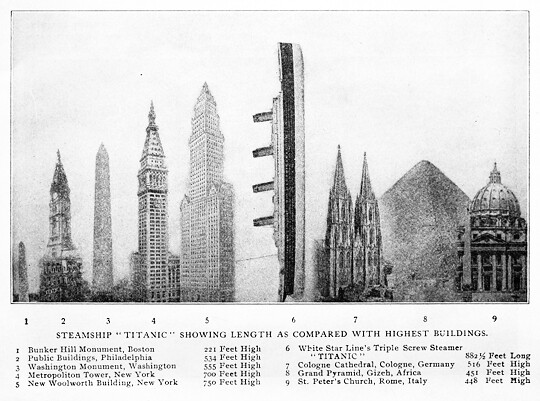

Illustration showing size of Titanic compared to the world's tallest buildings at the time, from Sinking of the Titanic, most appalling ocean horror (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray

We can imagine, then, the mythic consequences of building a ship which “God himself” could not sink. Naming it “Titanic” was only adding to the Hubris, and so the “ill-fated” liner duly finds its Nemesis at the hands of on iceberg on its first and only voyage. The reported size and luxury of the ship only adds to the moral power and significance of the tale.

But here is the vital point that is missed in pretty well every re-telling of the myth of the Titanic: nobody really called the Titanic “unsinkable” until after the ship had sunk. The Titanic’s alleged unsinkability was essentially a post-hoc, popular cultural invention to provide a moral –a meaning- to a terrible but ultimately random event. In this way, the historical Titanic became mythical within days of its sinking. The facts, even to this day, play second fiddle to the culturally preferred version.

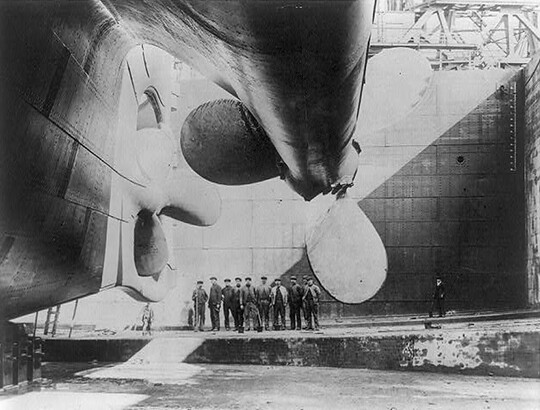

To substantiate this point, we must remember that the Titanic was in fact the second of three almost identical “sister” ships constructed by the White Star Line. The eldest was the Olympic, which preceded the Titanic into service on just the same route and with precisely the same safety features as her second-string sister. But the Olympic did not sink, and so was never dubbed “unsinkable.” The Titanic, on the other hand, went down and so the myth got to work, offering an “explanation” for the disaster –and explanation that would have made perfect sense to our Classical and cultural forebears. One hundred years on, therefore, our continued fascination with the Titanic reminds us that myth –unlike the actual Titanic –is alive and well today.

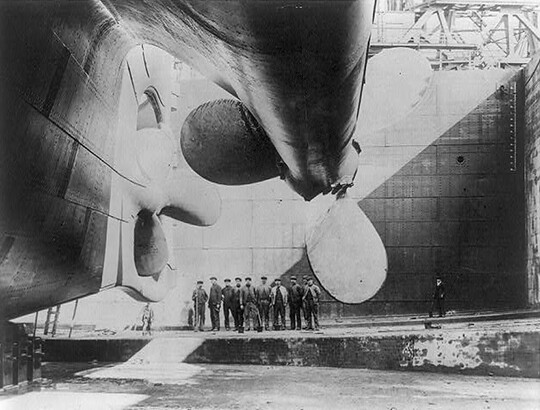

Propellers of the Titanic's sister ship RMS Olympic in drydock, 1911

RMS Titanic prior to painting, and prior to the A-deck promenade's being enclosed. Photographer: Robert Welsh

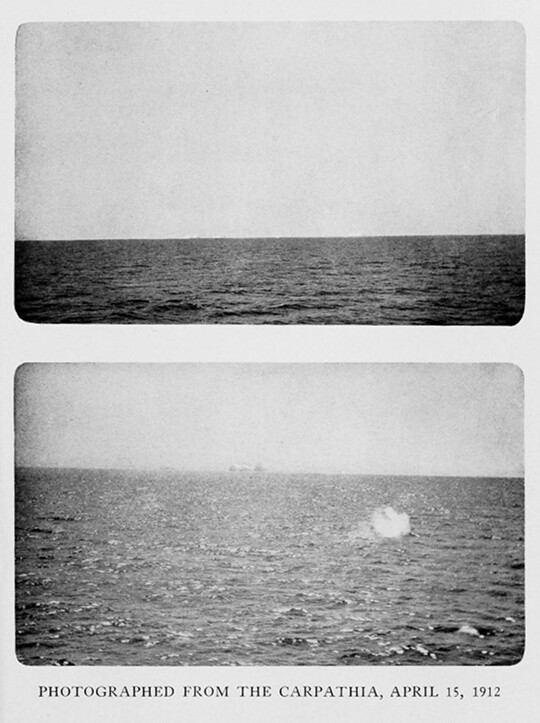

Detail from a photo showing the survivors of the Titanic on the rescue ship Carpathia, from the Bain News Service, 1912

Title page from Sinking of the Titanic, most appalling ocean horror (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray

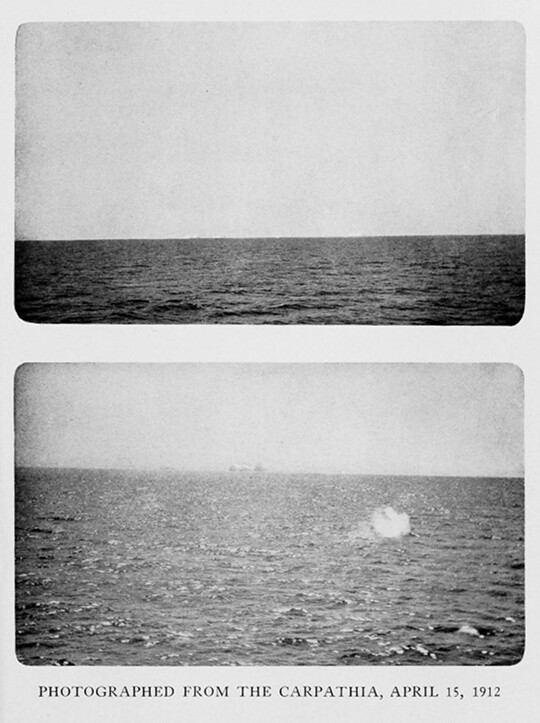

Photographs taken from the rescue boat Carpathia on the day after the disaster from Sinking of the Titanic, most appalling ocean horror (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray

Richard Howells is a cultural sociologist at King’s College, London. He combines a background in the humanities (Visual Studies at Harvard) and the social sciences (Social and Political Sciences at Cambridge). In 2004 he was Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Center for the Arts in Society at Carnegie Mellon University in the USA. He specialises in visual and popular culture, combining theory and practice to explore case studies as seemingly diverse as the Titanic and the humour of Ali G. He has additionally published on subjects including party election broadcasts, the ontology of the celebrity photographic image, and the life and work of Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince. His books The Myth of the Titanic and Visual Culture

and Visual Culture are now in their second editions, and a volume on controversies in the arts will be out later this year in collaboration with his colleagues at Carnegie Mellon. A detailed version of the argument contained in the article above can be found in the Centenary Edition of his academic study: The Myth of the Titanic, published by Palgrave Macmillan, London and New York, 2012.

are now in their second editions, and a volume on controversies in the arts will be out later this year in collaboration with his colleagues at Carnegie Mellon. A detailed version of the argument contained in the article above can be found in the Centenary Edition of his academic study: The Myth of the Titanic, published by Palgrave Macmillan, London and New York, 2012.

Links to Works

A film appearing to show a tour of the Titanic before it sailed can be seen here.

A great range of historical documents, including lots of newspaper front pages, relating to the Titanic can be found here at Wikimedia Commons.

Sinking of the “Titanic,” Most Appalling Ocean Horror (1912) by Jay Henry Mowbray

*A Tragedy of Speed: Sermon on the Wreck of the Titanic (1912), by William Dygnum Moss

*The Truth about the Titanic (1913), by Archibald Gracie

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!

Sign up to the PDR to get new articles delivered free to your inbox and to receive updates about exciting new developments relating to the project. Simply add your details to the form below and click the link you receive via email to confirm your subscription!