When Captain James Riley published in 1817 the account of his and his crew’s capture and enslavement at the hands of a group of North African tribesmen it became an immediate hit, readers being enthralled by this stark reversal of the usual master-slave narrative they were all so used to. Robert C. Davis, author of Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters, looks at the story in the context of other similar tales of Europeans being taken as slaves on the North African coast.

In 1817, the American sea captain, James Riley, published An Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig “Commerce,” Wrecked on the Western Coast of Africa , in the Month of August, 1815, with an Account of the Sufferings of the Surviving Officers and Crew, who were Enslaved by the Wandering Arabs of the Great African Desert or Zahahrah. More recently, Captain Riley’s memoire has been reprinted, though with a title that better fits modern sensibilities: Sufferings in Africa: the Incredible True Story of a Shipwreck, Enslavement, and Survival on the Sahara (New York: Skyhorse, 2007). This edition, along with a fictionalized version by Dean King, called Skeletons on the Zahara: A True Story of Survival (New York: Back Bay Books, 2005) enjoy respectable sales for reprints of a book nearly two centuries old.

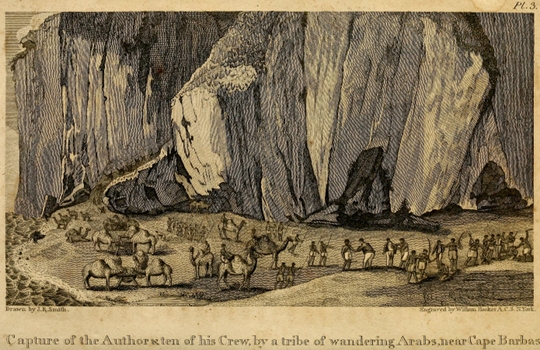

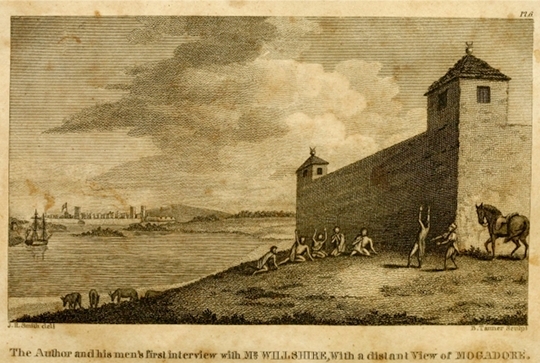

Captain Riley’s story is pretty well summed up by the original title of his book. While sailing from Gibraltar to the Cape Verde Islands, Riley’s mid-sized merchant ship got lost in the fog and wrecked on the west Moroccan coast. Trapped on shore and having run out of both food and water, Riley and the surviving crew threw themselves on the mercy of some passing Berber tribesmen, who promptly enslaved and carried them off into the desert. Abused, underfed, and overworked, the captives were nearly dead when their masters sold them to an Arab trader, who bought the Americans on Riley’s promise of ransom if they returned to the coast. The rest of An Authentic Narrative recounts the survivors’ slightly less brutal journey over desert and mountains to the port city of Mogador (modern Essaouira) and their eventual freedom.

Like many another adventure story, Captain Riley’s tale was essentially ghost written. The real author was Riley’s “respectable friend, Anthony Bleecker [or Bleeker], Esquire of New York,” called in as Riley himself put it, “to smooth down the asperities of my unlearned style.” Starting with Riley’s logbook, notes, and recollections, Bleecker applied his own “talents, judgements, and erudition,” and in under a year came up with a narrative rich in emotional, and even spiritual themes. In the process, Bleecker spun what had actually been a fairly short adventure – the whole story, from the shipwreck until the survivors’ return to Mogador, lasted barely two months, of which only the first three weeks were spent as slaves of the Berbers – into an epic tale of survival against both human and natural odds.

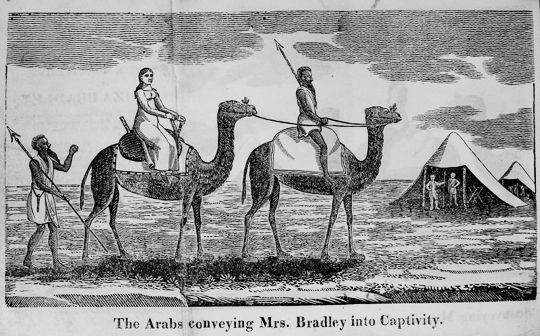

An Authentic Narrative was hardly the first Christian enslavement account – though it was nearly the last to be set in North Africa. Other unlucky travellers had also been shipwrecked on the wild Atlantic coast of Africa, south of Agadir, and a few of them survived to produce similar accounts. Paul Baepler, in White Slaves, African Masters (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), offered several tales of brutal treatment by such slaves, made worse, if possible, by the terrifying and bleak Saharan landscapes and by the desperate conditions they were forced to share with the nomadic Berbers, who themselves lived on the margins of survival. One was by Robert Adams, an African-American sailor whose ship ran aground in the fog in 1810, several hundred miles south of where Riley came ashore. Adams was a slave for over three years and with his wandering masters made it as far as Timbuktu. Another castaway, the American woman Eliza Bradley, supposedly spent eight months in Berber hands, though some have questioned her account as “a work of anonymous fiction that also plagiarizes large sections from James Riley’s best-selling account”.

The captivity accounts of Riley, Adams, and Bradley (if indeed she existed) were not typical examples of the genre, however. Far more common were the stories of European and American Christians who fell into the hands, not of nomadic Berbers but of Barbary corsairs. Of these we have scores of examples, published and unpublished, in languages ranging from Latin and Spanish to Italian, French, Portuguese, English, Dutch, German, and Icelandic. The earliest date back to Miguel de Cervantes, a slave in Algiers from 1575-80; among the last was the Italian poet Filippo Pananti’s Narrative of a Residence in Algiers, published the same year as Riley’s Authentic Narrative. The corsairs who captured them were professional slavers, ranging the entire length of the Mediterranean and (after 1600) out into the Atlantic, as far afield as the Cape Verde Islands and Iceland. These freebooters took their captives from merchant ships, fishing boats, and any village they could sack, selling them in the slave markets of Salé on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, or in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, on the Barbary Coast. Some captives – the very wealthy and many women — were bought by dealers who specialized in ransoming and were often well treated, more as hostages than as slaves. The great majority were properly enslaved, though, worked hard by their masters, regularly beaten and sold when they were no longer fit or profitable. At least an eighth of the captives were allocated to the state, its share in recompense for supporting the corsairs. They were set to work on state projects – building the harbor, or fortifications, digging in quarries, serving as longshoremen; or rowing in the galleys. Those sold to private masters were either used as house servants or farm laborers or rented out to potters, tanners, construction bosses, or water sellers. A lucky few managed run shops or taverns, paying their masters a monthly fee for the privilege. Women not suitable for ransoming generally ended up in the harem of wealthy corsairs or the ruling pasha, either as serving maids or concubines.

Illustration from William Okeley's Ebenezer: or, a Small Monument of Great Mercy (London, 1675).

Whereas Captain Riley experienced his captivity within the confines of a small and socially simple nomadic band, those Europeans taken to Barbary were thrown into crowded cities that teemed with myriads of slaves, free Christians, renegade Christians (who had “taken the turban”), Turkish janissaries, Jews, Arabs, Berbers, Greeks, and black Africans. In its heyday Algiers was immensely powerful, one of the richest cities on the Mediterranean, and, like Salé, a kind of merchant republic, run by the same corsairs who had grown rich through slaving. Each of those Barbary slaves who wrote about it portrayed different aspects of captivity – Francis Knight and João Mascarenhas portrayed life as galley slaves; Emanuel d’Aranda and Chastelet des Boys described many other kinds of slave labor, plus the daunting task of arranging their own ransom. Louis Marot and William Okeley, on the other hand, were fairly successful slave entrepreneurs, who also managed to escape from their bondage; the American Joseph Foss and the Italian Filippo Pananti wrote at length about the conditions of slavery during the institution’s last years. Many of these captivity narratives are now being republished. Those that have not are often available on line, for anyone who knows where to look.

Nevertheless, it is James Riley’s spare account of slavery and in its barest and bleakest terms that has consistently outsold all the rest of these narratives combined. Its American debut was soon followed by a British edition and within a year a French translation, titled Naufrage du brigantin américain El commerce, perdu sur la côte occidentale d’Afrique, au mois d’août 1815 (Paris: Le Normant, 1818); the following year saw a German version. Back home, An Authentic Narrative was republished no fewer than eighteen times by 1860. Like any best seller, the book also accrued its share of celebrity blurbs. Henry David Thoreau and James Fenimore Cooper both praised it, and, above all, Abraham Lincoln included it in his 1860 campaign biography – along with Pilgrim’s Progress and The Bible – as one of the books that had shaped his youthful development.

Detail of an illustration of a slave market in Algiers from Pierre Dan's Historie van Barbaryen en des zelfs Zee-Roovers (Amsterdam, 1684)

The modern appeal of An Authentic Narrative certainly stretches beyond its illustrious American readership – there have been two French re-publications in just the last two years. Its popularity says a great deal about the public’s new fascination with the Muslim world and the whole “clash of civilizations” thesis, which has so dominated political discourse since 9/11. Perhaps it is no surprise Riley’s story has taken a greater hold on the modern imagination than those set in the cities of Barbary. His austere and desperate tale revolves around a restricted cast of characters, like a Chekhov play – Riley himself and his few American comrades; their nameless handful of Berber tormenters; the Arab, Sidi Hamet, who effectively rescued them; and the English consul, William Willshire, who redeemed them and set them free. The simplicity and intimacy of Riley’s story – which closely resembles contemporary American captivity accounts, where settlers fell into the hands of American Indians – presents an uncluttered narrative arc, a Dantean tale of the descent of a lost wanderer into the hell of bondage and despair, only to rise again through a redemption earned by steadfastness. It is a tale fit for the movies (Dean King made a documentary), which may explain its enduring popularity in comparison with the more complex and subtle Barbary enslavement narratives, where victims and persecutors, the damned and the saved, the righteous and the foolish are often so much harder to tell apart.

Robert C. Davis is a professor of Italian Renaissance and pre-modern Mediterranean history at Ohio State University. He has appeared in a number of television documentaries, on shipbuilding, Carnival, and the Mediterranean slave trade, in addition to authoring numerous books including Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800 in 2004.

Links to Works

- An authentic narrative of the loss of the American brig Commerce, wrecked on the western coast of Africa, in the month of August, 1815, with an account of the sufferings of the surviving officers and crew, who were enslaved by the wandering Arabs, on the African desart, or Zahahrah; and observations historical, geographical, &c. made during the travels of the author, while a slave to the Arabs, and in the empire of Morocco (1817) by Captain James Riley

- The narrative of Robert Adams : an American sailor who was wrecked on the western coast of Africa, in the year 1810, was detained three years in slavery by the Arabs of the Great Desert, and resided several months in the City of Tombuctoo (1817) by Robert Adams

- An authentic narrative of the shipwreck and sufferings of Mrs. Eliza Bradley, : the wife of Capt. James Bradley of Liverpool, commander of the ship Sally which was wrecked on the coast of Barbary, in June 1818 … (1820) by Eliza Bradley

- Narrative of a residence in Algiers: comprising a geographical and historical account of the regency; biographical sketches of the dey and his ministers; anecdotes of the late war; observations on the relations of the Barbary States with the Christian powers (1818) by Filipino Pannetti

- Eben-ezer, or, A small monument of great mercy [electronic resource] : appearing in miraculous deliverance of William Okeley, William Adams, John Anthony, John Jephs, John —, carpenter, from the miserable slavery of Algiers, with the wonderful means of their escape in a boat of canvas … (1675) by William Okeley

- The adventures of Thomas Pellow, of Penryn, mariner, three and twenty years in captivity among the Moors (1890) by Thomas Pellow

- pdf online